Dallas, Texas

In August 2023, a 35-seat microcinema called Spacy opened in Dallas. It is located inside of Tyler Station, a factory built 100 years ago, that now operates as a “place where Oak Cliff Entrepreneurs, Creatives and Community Leaders meet and work.” There are two ways to get inside: the first is to go through the Oak Cliff Brewery which sits at the top of the building and snake your way down; or, you could go through the south side where there is a bit more parking and pass through the Oak Cliff Bike Synergy and other establishments. As you make your way, you will see signs that direct you to Spacy and eventually you will find a tiny spot that resides in what the leasing agent dubbed “the dungeon of Tyler Station.”

When Spacy opened, I was immediately attracted to it. The opening film was Anhell69, a Colombian documentary, an essay film about queer youth in Medellin. The director Theo Montoya narrates over his images, his somber voiceover, somewhat mumbled, establishes a funereal tone that the images never quite overcome, even if the people in front of the camera sometimes refute this gesture. While the film never quite convinced me, I did find how it becomes an update to Victor Gaviria’s cinema (eschewing his neorealist narrative path) rather moving. And the experience of attending a showing at Spacy intrigued me. I believe quite deeply in the big screen, in the way that it grants everyday images a monumentality that perhaps would not exist if you were to review them at home, in the way that it focuses your attention but also allows your eyes to wander. Watching a film at Spacy was something altogether different. The owner, Tony Nguyen, stood before us, talked a little about the idea of starting a microcinema, pressed play on the file on his laptop, and the projector came on. He adjusted the volume with a remote control and then turned off a light inside the room. Just the other day I remarked to someone that watching a film at Spacy is a very intimate experience. You feel connected not only to the venue but also to those around you because you understand the gesture of exhibiting a film differently than you would at an AMC or Cinemark. Earlier this year I attended a screening of Patrick Tam’s My Heart is that Eternal Rose where I was the only person in the audience. When I had to go to the bathroom, I paused the film myself.

There are not many options for cinephiles in Dallas. The festivals never have more than one or two films in their lineups that interest me (the Dallas International Film Festival can be understood as an exercise in shoving as many uninteresting documentaries into one space as possible, while at the Oak Cliff Film Festival everything is a potential cult film with titles like Aliens Abducted My Parents and Now I Feel Kinda Left Out). On the theater side of things, we have some Alamo Drafthouses, but the curatorial sensibility is absolutely alien to me (I will note here that I’m not opposed to eating food at a cinema!). We have a Violet Crown (used to be the Magnolia), an Inwood Theatre (I’m not sure what else they play besides The Rocky Horror Picture Show), an Angelika Film Center (the one in Plano recently closed down). What I’m getting at is that Dallas usually gets your normal arthouse releases. But once we enter the world of Cinema Guild and Grasshopper releases and things of that nature, then Dallas becomes a tougher market. The Texas Theatre in Oak Cliff has carved out an interesting identity over the last 10 years, but their appetite leans toward cult and genre (they recently exhibited 10 Things I Hate About You in 35mm). What does this look like in practice? Well, there’s absolutely no guarantee that we will get the Edward Yang restorations over here. And the less said about the Dallas Museum of Art the better, an institution which only pays attention to cinema if it is related to one of their exhibitions – their retrospective of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema back in 2018 is still the best programming I’ve ever attended here and nothing like it was ever attempted again.

This is why when the first programming was announced for Spacy I just about lost my mind (Passengers of the Night, Yasuzo Masumura, Jang Sung Woo). And then there was a retrospective of Axelle Ropert, a Lucky Star axiom. I was supposed to introduce one of the films at this retro, but unfortunately nobody showed up. I ended up talking to the founder Tony about an idea.

The Latin American Film Festival of Dallas

In Dallas, we have festivals related to environmental films, black films, South Asian films, Jewish films… But no festival dedicated to Latin American cinema (well, there was one that started in Denton and then moved to Fort Worth and whose lineups seem collected from random Film Freeway submissions). The fact that a city like Dallas, with its pronounced Hispanic population, did not have such a festival struck me as odd. I saw an opportunity.

Why don’t the festivals of Dallas have a relationship with the most innovative films from Latin America? I gave an example. A film like Trenque Lauquen by Laura Citarella, by almost all accounts one of the most notable Latin American films of the last few years, will not exist in Dallas screens – I was told by the DIFF artistic director, James Faust, that the screening fee for this film was too high and so the choice was made to highlight other films. And even though the film is distributed by Cinema Guild it will not come to any of our theaters (although that’s a separate problem). I submitted to Tony that the allegiance of Dallas’ film institutions to North American festivals such as SXSW, Sundance and Toronto, prevented them from going after better, more interesting films. The conversation with Tony revolved around these issues, and from these conversations he encouraged me to pursue the idea of starting the Latin American Film Festival of Dallas. A once-a-month screening series was discussed, but there was something very alluring, something much riskier and therefore more seductive, about the idea of a film festival that I couldn’t set aside. Perhaps because I’ve always nursed this fantasy of attending a festival like Berlin and Cannes and gorging on their programming…

The act of programming is something foreign to me. My experience with festivals has been as a pre-screener, seeing Film Freeway submissions and chiming in on what I thought (always shorts due to the smaller time commitment). Sometimes the films I recommended were picked, sometimes not. I was not a part of the discussions and negotiations. I viewed everything from a distance. And I was rarely privy to the films that were outside the Film Freeway system. How to put together a program?

Some decisions must be made. The festival was tentatively scheduled for the end of January, though we later moved it in order to avoid clashing with another festival – a bit arbitrary, but I privately relished the idea of being against Sundance. Oak Cliff lasts around four days, it’s a weekend festival, and we figured that was the right scope for our first edition. They have multiple venues; we have one. This automatically limited the number of films we could show. We did the calculation and at most we could play something like 12 films. Since our festival revolved around a geographical survey, I immediately made a list of the countries and festivals to research.

These steps are a bit bureaucratic and administrative, but they’re necessary – a website was made in order to be more official and with it came its attendant domain name costs and hosting, an Instagram page (crucial sometimes for contacting filmmakers and production houses when email doesn’t work), a logo and a Festival Scope Pro account. The last one indeed proved to be quite useful in researching and reaching out to filmmakers.

While I am new to the act of programming, I have ideas about it. I believe it’s always an act of cinephilia. I remember reading an old article by the critic Robert Koehler which stated that film festivals have one job and that it’s to defend cinema. I remember another interview I read with Roger Koza stating that as a programmer you have to propose and defend an idea of cinema. While I certainly believe this to be true, there is also a much more pragmatic side to things. Logistically, this festival would not be possible without having a venue such as Spacy behind it. The reason is two-fold: first, we don’t have to pay to secure the venue since the venue is directly involved; second, because of the size of the theater, because it’s our first edition, we are able to negotiate screening fees much more freely. If a film was ever too expensive for us, then I believed that we could move on and find something else. We accept our marginality in that sense.

There are many other things to keep in mind. Which filmmakers/producers/distributors respond to our emails? A film like Leme do destino by Júlio Bressane premiered at the Rio International Film Festival and all my attempts to to contact the team behind it went nowhere. I reached out to a Brazilian film critic who had seen the film and asked how he had done so – he saw it at Bressane’s house! I moved on and looked for other options. Which films are being held back for better international premieres? Some films have premiered at a festival in their own own countries, but want a splashier international premiere, such as Rotterdam. That’s completely understandable. Filmmakers and producers have to do what’s best for their film. Our festival, LAFFD, is a very small affair with no prestige. I moved on. Which films will already be streaming by the time of the festival? We inquired regarding Rodrigo Moreno’s The Delinquents, for example, but it would already be streaming on Mubi by the time of the festival. And, in a twist, it turned out that the film played theatrically in Dallas (Mubi has steadily increased their presence in the theatrical market). Do I have time to watch everything I want to watch? I put in a fake selection committee on the website, but really all the viewing was done by me, but the problem was also that because we started this process at the end of summer heading into the fall there wasn’t that much room to explore and take our time. Decisions were made rather quickly.

Some of these things are out of our control and influence the program, but the original bet was always that we could build an interesting program and have this not be a super expensive proposition. And while I consider the programming to be formed by my cinephilia this is something that’s different from programming based on my taste. For example, I had to confront my bias against documentaries and wade into those waters, and as a result half the program consisted of documentaries. But my cinephilia informed the documentaries we chose – we went against documentaries with easily digestible subjects, with talking heads, with pop culture. We chose documentaries that are acts of exploration. In the case of our choice from Brazil, The Invention of the Other, the documentary form becomes almost an adventure movie.

In other matters, I let my cinephilia guide me much more. The example of Mexico is illustrative, as it was probably the hardest country to program. Right out of the gate, I already knew I wasn’t interested in certain filmmakers (like Amat Escalante, Tatiana Huezo), or certain styles (any miserabilist clone of Haneke). We did our due diligence by inquiring about arguably the biggest film from Mexico, Totem, but by the dates of our festival the distributor was only looking for theatrical engagements. In the case of a film like Desaparecer por completo by Luis Javier Henaine, the producers only got permission from the studios to do a couple of festivals (I originally became interested him in because of his previous film, Solteras). By the time Mexico has to be finalized the program already had a lot of documentaries, so I prioritized fiction films. The final choice, Malvada, was a film I did not initially consider – too commercial, already streaming – but ultimately it made sense. If we wanted to propose an alternative vision of Mexican cinema, then we truly had to look elsewhere. I relied on my cinephilia and chose a film I had written about for Lucky Star. The choices were always a mixture of intuition and rationality.

Youth

The idea behind the festival is somewhat opportunistic (nobody else is doing this), but also one that emerged from a sincere desire to make an ideal festival a reality. What does this look like? First, a festival is where the films are what’s important, not parties, sponsors, or anything else that distracts from that focus. A festival is an event, yes, but it’s an event that makes possible an encounter between a viewer and a film. Anything we do should be towards making that possible.

Due to the small amount of films in the program, the selection truly became a proposal, rather than a random collection of films. In my initial daydreams, I imagined something like 25 films with around five sections – a section for more mainstream films, maybe with more stars (a film like Argentina, 1985 would go in this section); a section for new filmmakers, either debuts or up to their third film (something like I Have Electric Dreams could go here); a section for more experimental films (maybe The Great Movement ); a section for films by masters (would we perversely put a film by Jose Celestino Campusano in this section?); and then a section for repertory films. But this type of scale was impossible for us to start with. Trying to find the variety in Latin American film practice becomes very difficult if we only have those eight spots, as you also have to keep in mind that you’re doing a geographical survey. In practical terms, there are eight contemporary films and three repertory screenings. Three films from Chile, two from Argentina, two from Mexico, one from Brazil, one from Colombia, one from Dominican Republic and one from the USA. None of the films are truly radical propositions (I wasn’t necessarily interested in programming experimental films but I also didn’t rule it out), but they operate in a zone where they tweak established rules for their own purposes, or better yet create their own.

What idea of cinema does LAFFD defend? What sort of proposal does it make to its audience? Almost by chance, the lineup became a bet on youth. The majority of the new films selected are either debuts or second films. I must admit that when we started I had imagined more established names would be in the mix. For a long time I thought Martin Rejtman’s La Práctica would be a shoo-in. We need to have an established master! But other films called out to me. Its sense of humor felt a little too dry, its affect seemed all wrong for the lineup by the time I got to see it. I surprised myself and went another direction. Many of the films themselves deal with themes of youth. New directors filming new generations, discovering themselves. It’s there in the group portrait in Deaths and Wonders, which necessitates a splintering off to find the individual (this process of self-discovery is done through poetry). It’s there in Ramona where questions of representation are discussed collectively, and the subjects of the documentary take over to make manifest their own portrayal. It’s there in a film like La Bonga, where the young generation is returning to a place that they’ve never been to, a place they’ve only heard about. The key film in this respect is Martín Shanly’s About Thirty, our opening night film. It is a millennial comedy, perhaps, but a resolutely social one, about the struggle of being a young person out in the world. The main character Arturo, played by the director, is someone who struggles in everyday normal interactions, seems to say the wrong thing, and doesn’t quite know how to put people at ease. He’s unable to temper his own discomfort and anxiety (weed helps a bit). The film finds him attending the wedding of his former best friend, but then a car crash causes the film to be unstuck in time. With each ridiculous and pathetic scenario, we are thrown into the past, into a series of flashbacks that get progressively sadder. As we see Arturo getting progressively more drunk at the wedding reception, we understand deeply the disconnect between him and his family and friends. This is a film about reaching a certain age, when our awkwardness is no longer endearing and everything is embarrassing. The fact that this is channeled into a comedy is part of the film’s secret charm.

Another idea was that the films should actually depict Latin America. Films like The Human Surge 3 and Eureka are undoubtedly made by important filmmakers, but a lot of their runtime are given over to depicting other parts of the world. This is not said to dismiss those films, but rather to say that these particular films felt at odds with the mission of the festival. The downside to this decision is that this might’ve been the one chance to see them in a theater in Dallas. But, then again, we always break our own rules. We included the American documentary Hummingbirds in the lineup because it had somehow never played Dallas, and because I wanted to try and find a film relating to the Latin American experience as it manifests itself in the United States. It seemed perfect because the film takes place in Texas, at the border between Laredo and Mexico, and it puts into question many of the most pressing issues of our age and does so with a sense of humor. This offhanded contemporaneity should not be dismissed. If we can see ourselves onscreen, our lives, our houses, our people, then it seems to me that it becomes much easier to address a collective imaginary, and from there do all sorts of things.

But then there are films that didn’t quite fit into whatever neat categorizations I had regarding this idea of cinema that the festival proposes., or any of my self-imposed rules. Bruno Jorge’s The Invention of the Other was by far the longest film in the festival (another self-imposed rule: try and look for shorter films!), is not really about youth, and does not put forward an experience of Latin America that its audience in Dallas might recognize. It takes place deep in the Brazilian jungle and depicts the journey to meet a tribe who has never made contact with civilization. What does it mean to invent an other? And who is the other in this scenario? Is it the tribe, the Korubo? They who have no awareness of cinema, of cameras, of our civilization? Or, is the other the ones who make the expedition to find them in the jungle? They who are government employees and must leave society behind, go toward an unknown, and witness something no one has ever quite seen before. They seem as distant to us as they are to the Korubo. One definition of cinema could be that it’s an encounter with an unknown, another consciousness. The Invention of the Other dramatizes this encounter as an adventure – dangerous and joyous in equal measure. In the last 30 minutes of this film, we forget cinema for a while and marvel at the sheer oddity of the humanity in front of us. I hoped that the audience would have a similar reaction.

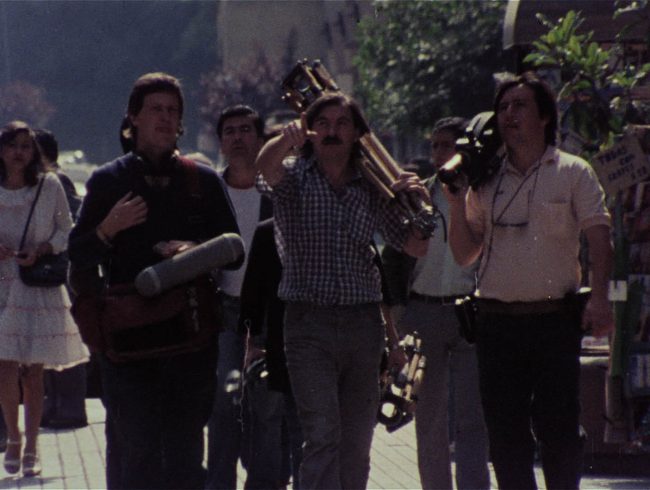

When it came to the retrospective choices, a couple of things were on my mind. First, the Locarno retrospective dedicated to the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. In a sense, I wanted to put forward a vision of Mexican cinema far away from the one we’re stuck with today, full of violence and horror, and rather re-establish the glory of this national cinema (a ridiculous and foolish ambition!). The Julio Bracho film, Llévame en tus brazos, quickly announced itself as the best candidate. This is a rumbera melodrama starring Ninón Sevilla as a woman who moves in with the rich sugar mill owner in order to repay her father’s debts, thereby leaving her younger lover. The camera loves Sevilla, always in awe of the way her face and body project emotion (the dancing scenes are perfect). She moves from one melodramatic role and scenario to another (fisherman’s daughter, dancer, kept woman, movie star) with aplomb and seems like the auteur of the project (she got Bracho and Gabriel Figueroa on board and paid to have the film finished). She dominates the film. And in late 2023, when this program was being put together, the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup was around the corner. I thought it would be good to put forward films that showed life under the dictatorship, but did so in a way that avoided violent sensibility. The films of Ignacio Agüero seemed the perfect candidates and due to their length it became a little mini-program. Como me da la gana and One Hundred Children Waiting for a Train are films where the surface signifiers of politics remain almost invisible, where there almost no slogans, no discourses – the subject matter appears to be so frivolous that it seems ridiculous to object. It seemed imperative to have a retrospective offering, but with the room at our disposal it seems hard to really make something very coherent with it. This seemed to me the biggest place to improve upon.

We ended up pushing the festival back to the first week of March to give ourselves more time to organize and to advertise. We also received a grant from the city of Dallas that covered all of the festival’s expenses. Thanks to the grant, the gamble was rewarded – at the very least, we wouldn’t lose money on this. The grant process itself was interesting as it required us to pitch the project in a very non-cinephile way. The language required was quite new to me: how will the festival positively impact the community? How will the programming provide cultural and educational benefits to Dallas citizens? How will the festival create a space for discussion and enrichment? This was all very far from me! But asking the questions was helpful in thinking through the implications of the programming and to question why we were doing what we were doing. After all, it is not a festival dedicated to my own taste. We must try and reach others. Some of the things that happened in this last period before the festival are purely organizational: we set up a mixer before the Friday night feature at the Oak Cliff Cultural Center which required catering, food, tables, beers, wine, a playlist, conversation with visitors; we submitted the event to various activity calendars in Dallas; we organized files, trailers, Q&A’s; I learned how to run the projector, how to set up the files, how to run the POS system at the theater!

Post-Mortem

Do I analyze this as a cinephile? As a programmer? As the organizer of an event? First, the raw facts. Four films sold zero tickets. For one of them (Llevame en tus brazos) a family member came to the screening and we watched the film together. For another film, we sold one ticket. The most successful film was Malvada, which showed Friday night at 9pm, perhaps a prime spot for such a purely entertaining film. The experience was wonderful and seeing the film with an appreciative audience made me like it even more. And the same thing happened with About Thirty. The audience was not as big, but the energy in the room was wonderful (someone remarked that in my Q&A with Martin Shanly I was trying to subtly ask him if he was rich!) There was a nice discussion with two of the audience members after the screening of Ignacio Agüero’s films. The mixer we held was sparsely attended and some of the people who showed up didn’t go to any of the films (I admit that playing host and speaking with everyone was a bit exhausting). Worth the effort? I don’t know. But I’m told that events like these are necessary. Perhaps how we do them will need to be rethought. Second, what does success look like, in any of the above mentioned categories? I supposed sold-out screenings for every film would’ve been the best possible outcome, but I never fooled myself into thinking that was going to happen. But, if we see success by the number of tickets sold, under which of those categories am I making that judgment?

Let’s step back a bit. Nothing went wrong. There were no problems with the files, no problems with the sound, nothing that could be termed an emergency. Every screening started 10 to 15 minutes late, but that’s the standard operating procedure for the venue in order to make sure that any stragglers are able to find it. But there were a few things that were missed opportunities. We didn’t maximize the proximity that Spacy has to the Oak Cliff Brewing Company in order to advertise, to host events, etc. Perhaps this place would’ve been a better place to host the mixer? We had a tentative plan to do something there on the final Sunday, but it was never formalized and we didn’t announce anything. We probably didn’t push hard enough to get Q&A’s from all the filmmakers. I interviewed two filmmakers, but a couple of them were probably gettable/approachable and I should’ve been more hardnosed about it (one of them was in the Amazon so I couldn’t do much about that). Marketing was a bit of a crapshoot. The interviews we did for a couple of outlets were published without almost any cross-promotion on Instagram. You would’ve had to go to their website to find the interviews. We also didn’t do enough to get on the radar of Spanish-speaking outlets. And the flyers we printed out were too big to easily distribute which made the whole enterprise seem like a waste of money (personally I had very little time to go out to distribute flyers). I wonder if less of an investment in printed advertising and more trying to explore internet advertising (Facebook, Instagram) might’ve gotten us a better bang for our buck (I still want to frame our poster, make no mistake).

From a programming perspective, obviously if you have a film with zero sold tickets you start to have doubts! Clearly it was a failure of marketing, but was there something that made the films not appealing? I theorized that the trailers for the films didn’t make them seem particularly exciting (Hummingbirds inexplicably did not have a trailer at that time), whereas Malvada’s trailer is very punchy and accessible. I believe all the films we chose are worthy and interesting, but I will concede that some films were unlikely to draw a big audience without the festival first establishing itself to its audience and earning trust regarding its selection. Should I have prioritized trying to get bigger films like The Settlers? Was it a mistake to ignore a film like The Echo? Due to the size of the program, real choices had to be made. I couldn’t include everything. And the point of the festival wasn’t just to get all the big hits of the festival circuit. During one of the introductions, I remarked that LAFFD was about offering an alternative view of cinema, and thus it made perfect sense that it should be hosted in an alternative space for exhibition. It’s the path we chose. I can’t complain too much. Regardless, it was demoralizing to sit there while nobody came to various screenings. And, it should be noted, that since Spacy is also a fairly new venue, it is still building its audience. Empty screenings do unfortunately sometimes happen.

Let’s think about this as a cinephile. Part of the most personal and selfish idea of the festival is that I wanted to make my cinephilia an almost physical thing – I wanted it to exist in the real world. And thus, LAFFD is an extension of my cinephilia. It’s defined by it and, perhaps, limited by it. But programming the festival was an attempt to go beyond this limited perspective and reach others. Did that fail? What I will submit is that I don’t believe the festival betrayed my cinephile spirit. Whatever internal compromises were made, I believed they were made under that lodestar. Most importantly, the festival was about the films. I can imagine a scenario where we add extra things, other events and things of that nature, but I can’t see myself accepting something that distracts too much from the films. If a festival is a social experience, then it’s one that has as its common meeting point a film, a collection of films, sounds and images. Whether you stick around to discuss the film afterward or head straight home, what’s important is that a film was seen and experienced. Anything else should be additive to that basic fact. As a cinephile, I judge the first edition of LAFFD a success in those terms.

But, all of this is quite abstract. Perhaps the most basic qualification for success is that we’re planning on doing another edition next year. I’ve already started watching films and making spreadsheets. It’s a little embarrassing to admit above that some things didn’t go great, but it would also be delusional to put forward a perfect picture. It was our first year. We have many things to improve upon. I only feel bad people didn’t get to see some of the films we chose.

To end with, LAFFD is an extension of the same impulse that drives my work with Lucky Star. There’s no sense in waiting for spots to open up in dying institutions, or pretending that this is a true career path for myself. What’s necessary is to create your own space, away from careers, away from discourses, away from advertising – cinephilia begins there. To write about Malvada and then see it with an audience was never part of the plan. But it makes sense now. Jacques Rozier once said that cinema is a question of risk and desire. Thus the act of sharing a film with someone else, writing about it, exhibiting it, is part of the same continuum. I believe that same risk, that same desire, was there with me in the audience in Spacy. It was there as I, slightly tipsy, introduced the opening night film, About Thirty; and it was there as I waited impatiently for someone to come to our Saturday showings. It’s here with me now writing these words. I hope it will be there in our second edition in 2025.

The first edition of Latin American Film Festival of Dallas took place February 29th to March 3rd, 2024. You can review the lineup here.

3 comments