In Praise of a Castaway: Jacques Rozier

by Rodrigo Moreno and Alejo Moguillansky

*

The scene is that of a not-so-young playwright and an already old filmmaker of what was the New Argentine Cinema. The playwright complains that his plays aren’t as recognized as those of his colleagues: “Everyone likes them, but no one really takes them seriously.” He compares himself with his contemporaries and, in fact, the plays of those he considers his peers are infinitely more celebrated than his own. The old filmmaker looks at him and reveals something that the playwright had never thought of: “It’s because you make comedies. Nobody takes comedies seriously.” The playwright finally understands his tragedy, and takes refuge in that talisman that has just been given to him.

* *

How is it possible that the film that was taken as a bastion of the nouvelle vague has become an asylum for a cursed cinema, a marginal film remembered only by a handful of suburban cinephiles? How is it possible that the film presented at Cannes 1962 by Godard and Georges Sadoul under the maxim “Anybody who hasn’t seen Yveline Céry dance the cha-cha looking straight into the camera is unqualified to continue discussing cinema on the Croisette!”, whose performers were interviewed by Truffaut in front of the Palais to then use those fragments in the trailer, that Rohmer put on the cover of Cahiers du Cinéma while he was editor-in-chief for the special issue dedicated to the nouvelle vague, how is it possible that the course of this film and the one responsible for it have led to its somewhat average position not even comparable to that of our playwright in the previous paragraph?

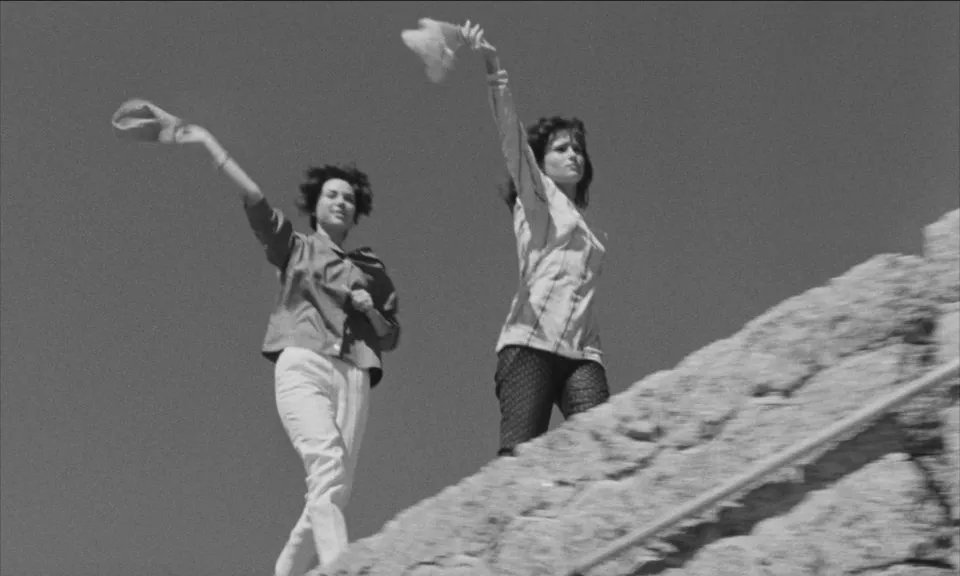

“Adieu Philippine is, and I write this without envy, the youngest film of the new wave,” said Godard about that film, which some of us return to again and again, as if it were an amulet, a landscape from our youth that one can’t get rid of. From the beginning of the film an intertitle gives us a date, “1960 – sixth year of the Algerian war.” The story begins: a young Frenchman is waiting to be summoned to the battlefront, where he will leave from the port of Marseille. After trying his luck working in television or at a suspicious film advertising agency, he gets himself fired from his work and embarks on a trip dedicated to pure leisure with two girls he meets. The film becomes an endless drift sustained by the miraculous wit of each scene, but also by the expiration date imposed by the departure to war of the young Michel Lambert, played by Jean-Claude Amini in the only involvement he had in film throughout his life.

There lies a first clue: drift as part of an extraordinary time. Fiction is born not so much from what is stated or what happens in the shot, because the shot is more like a documentary about a fiction whose foundations (if one can speak of such a word regarding Rozier) are, on one hand, its absolute free will, and on the other, its perishable condition. A fiction that resembles, finally, a landscape of affective memory, situated probably at a summer horizon where the light, the sparkle in the sea, and the distant sound of waves enjoy something resembling meaning. That extraordinary time, an equal distance between waiting and freedom, becomes narrative material for an extended, irresponsible and capricious adventure. As if once this limbo was achieved, which Rozier’s characters usually inhabit, would be loose as meters and meters of film pass through the chassis.

The story surrounding the film is no less erratic: after two short films, Rentrée des classes and Blue Jeans, Godard convinces Georges de Beauregard (producer of his own films, but also those of Rohmer, Demy, Varda, Melville) who was looking for films “about youth.” The initial project was a self-proclaimed musical comedy, Embrassez-nous ce soir, that would be released the following year and, in fact, the contract they sign in 1960 contemplates the making of that film and not another. Rozier, in an act comparable to his behavior as a storyteller, grabs the rudder and turns to a draft that he had written in mid-1959 with his wife and that they had abandoned to avoid problems with censorship. That draft called Les Dernières semaines is the seed for Adieu Philippine. Filming took place in 1960 (the war would end in 1962, the year of its premiere in Cannes) between Corsica and Paris, filming 40,000 meters of film with several cameras, much to De Beauregard’s dismay. It’s a shoot plagued by budgetary problems, with portable sound equipment recording in a completely chaotic and non-synchronous manner. Due to the lack of a script, they spend five months in post-synchronization reading the characters’ lips. Beauregard reaches his limit: he abandons the film, which will only see its premiere in 1963, after the war was already over. The commercial release is catastrophic. Only in 1971 does Rozier manage to film a feature film again: Du côté d’Orouët.

* * *

Let’s think of his peers, his contemporaries, his countrymen: Godard, Rohmer, Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer, Resnais, and those closer to him, Eustache or Pialat. Where does Rozier rank, among all of them? Anyone could say that the low status of his art is incomparable to the great works that those others have left behind. But, unlike any of them, Rozier embodies the tradition of French comedy the way Jean Renoir understood it, relying on everyday adventure, mischief, and the charm of the actors. We could conjecture that having been the assistant director on French Cancan was decisive to his cinema.

But a feature of modernity is that it deconstructs the laws of classic cinema. Comedy, according to Rozier, succumbs to the exacerbated development of its actions, extending itself into time and space (perhaps Rivette’s misdeeds are their closest relatives to the new wave). In his desire to deform narrative, Rozier understands comedy not as a genre of synthesis but, on the contrary, as the possibility of settling into the misunderstanding or the entanglement that comedy naturally proposes and forcing it to the point of implausibility and incongruity in order to, once there, move forward?

Think of Rozier as Bresson’s negative: the complete form that Bresson achieves in the meticulous and millimetric portrait of actions (a certain idea, a just shot), in Rozier is manifested in a completely savage way. There are no millimeters because he does not provide any measuring tool, there is no thoroughness because there are no punctuation marks. What is just in Rozier does not lie in the distance nor the speed of the movement; neither in the austere or sufficient expression of the sound, nor in the off-screen as the evocation of a mystery. The just in Rozier finds its footing in the duration of the scenes. These remain, to use a chess term, in check by the desire to exhaust them until they offer something new. What is filmed becomes palpable not because the real is manifested through a documentary device, but rather because things naturally last a certain time. The time that passes at the Maison du Café in Adieu Philippine brings us closer to the place, makes us present. The same happens with the arrival of the vacationers in Corsica, or the recording of ‘Montserrat’ (a sort of TV film that interrupts in the midst of the story of Adieu Philippine, where Michel is working as a cable puller). The time in which Ménez cooks with the three girls in Du côté d’Orouët makes us accomplices in the scene. The improvisation that starts in daytime with “Meu caro amigo” (the Chico Buarque song) and turns into a generic, outdated samba in Maine Océan (one of its best sequences, and one of the best musical sequences in the history of cinema) would give the impression that the Rozier method’s policy is to continue filming, not until something comes to light, but until the nonsense that inhabits each scene of his films finds a poise, a complicity in us. The real, if we may use the term, manifests itself, in the Rozier method, by starting to let the characters live their lives within the shot that, despite never being a sequence shot, would seem infinite.

* * * *

– ‘It must be said: the only film where that shipwreck reaches its splendor is Adieu Philippine. I’m not really sure if, on any occasion other than that film, Rozier reached that virtuous failure’, said one of them.

– ‘Maine Océan’, answered the other.

– ‘The character of Petitgas in Maine Océan is impossible.’

– ‘That actor who plays Petitgas is Yves Afonso. In Godard’s Masculin Féminin he is one who stabs himself at the pinball place.’

– ‘In Maine Océan that actor is permanently offside. He fails to escape a burlesque tone that takes all the scenes that have him as a pivot to a zone of infinite mediocrity.’

– ‘That tone is inherited from no other than Renoir.’

– ‘As well as the idea of filming with several cameras.’

– ‘But what Rozier really inherits from Renoir is the perseverance in the pictorial register of a body in a determined space. Or, more than pictorial: documentary. In this case, those two words seem synonymous. And the comedy, the entanglements, the acting incarnation of that is what, time and time again, seems to be pushing in a direction that is not that failure, but rather being functional. A functioning that, precisely because it wants to be effective, collapses to pieces.’

– ‘Perhaps Rozier’s mistake is working with a comedian. Let’s take for example: The Castaways of Turtle Island. I fear that Pierre Richard never understood the language of the film. He does seven more times than what is asked of him. Basically, he does anything that comes to his mind, as if the duration of the shot were a race to go through ideas and specific occurrences. Once one is finished, he starts with another and so on. Rozier’s lack of reaction on that matter is strange.’

– ‘Except in the very the long scene in the bed with the girl at the beginning of the film, where he achieves some sort of elongated and poised action through time.’

– ‘I will concede that scene. The rest of the film is dedicated, like a clown, to specific actions with specific effects, which are diluted and fail with the kind of language and humor that the scenes propose. In the shots where the film finally relaxes, either due to fatigue or laziness, or thanks to a lack of a playing field where it can test its inventiveness, that’s where the film triumphs. As if the humor of the film materialized more in the perplexity of being waiting for Godot.’

– ‘In this sense, the Sancho Panza of the film is the co-worker’s brother who ends up traveling with him to the island, who in acting terms proposes absolutely nothing more than being in a state between deceit and idiocy, is infinitely more effective. Somehow it makes me think of the language of the films of Albert Serra, where what catapults the fiction is a mere documentary presence, and the capacity for a portrait that the camera provides. A fiction which is indiscernible from a body’s being in time, where specific things are diluted into an ocean or plateau. What is truly compelling is that state of being, that perplexity, the erratic comings and goings, without a future, with the group of tourists. Any attempt at an accident, at a gag, of a specific occurrence will be vain.’

– ‘Tati had understood some of that: the perseverance to concentrate on the development of the gag, but avoid its punchline at all costs,’ the playwright concluded.

The old filmmaker couldn’t avoid an analogy between that lack of a punchline to the gag that the playwright referred to and the lack of recognition that his friend complained about – although he had the delicacy to not say that out loud.

* * * * *

Two constant motifs in the cinema of Rozier: the sea and its elemental interpretation, tropicality. The mambo, samba, and calypso are the music that sustains the frenzy to which Rozier aspires to as a comedian and, at the same time, results in an aural ambience that places the story in a setting of party and leisure. The tropical element in his films is a goal, an exotic port to reach even if one never arrives (the Rozierian narrative consists, perhaps, of never arriving). The life on the beach as a form of subsistence exceeds the plot of Du côté d’Orouët and the subsequent film, The Castaways of Turtle Island, and establishes a pattern that is repeated in one way or another in each film. Sailors, fishermen or vacationers will be the ephemeral companions of each journey. Like a Cousteau without a compass, Rozier explores the maritime life with the perseverance and curiosity of a naturalist who gets fascinated by the species in front of his eyes. Rozier would seem to not conceive cinema without the sea and, probably, does not understand the sea except through cinema.

What is the sea to our filmmaker? Perhaps it is not a poetic figure, nor an abstract image. In his features and shorts, the sea, the beach, is always, in narrative terms, the escape route from the mundane noise; but, mainly, they are the place where the rules of orderly life are meaningless, where an unlimited existence is possible. In those nonsense coordinates, Rozier films the seduction between bodies, he films music and dance, he films silly pranks, he films the complicity of friends, he films boats and sailors, he films fishermen, he films the joy of a detour and the absence of plans. In short, he films an idea, simple and happy, about life on the beach: the meeting point between men and women who are willing to exercise their freedom there.

* * * * *

If in the early films of Godard the editing can be thought of, among other things, as a tool that intervenes on the surface of a shot, in Rozier’s cinema the surface where work is done is rather the scene itself. There is no respect or interest in the shot as a dramatic or realistic unit. It is worth asking if it was the modernist filmmakers who have made the shot their material, or it if it was the study of those films that considered the shot as the field for all the battles in cinema. The editing in those first films by Godard, but also those by Truffaut and Rohmer, takes the form of cuts that burst into the shot under the guise of interventions, ellipses, hiatuses or, finally, false continuities. The curious thing about Rozier is that the editing, both in his first short films Blue Jeans and Rentrée de clases – clear preparations for his first film – and in Adieu Philippine itself, behaves in a completely casual manner, under a modernity fixated on its purely musical aspect, and with the irreverence and impunity of a teenager as the only aesthetic policy. Here it is not the editing’s task to interrupt or leave a shot in suspense, but rather the internal editing of a scene is more concerned with generating a duration that overtakes the action and floods the scene with a stagnated temporality; in other occasions, however, it is governed by metric complexes that are arbitrary, and that seem to have their pillars in popular rhythms applied to the editing. To put it more simply: in these second excursions he edits the scene with the tempo of a, for example, a cha cha cha percussionist, turning the shot into pure materiality, a pure temporal asset on the verge of becoming cinematographic music. In both instances, the shot is just a fragment that owes its duration not so much due to its internal ontology, but rather to its status as a raw piece of the cinematographic register that will become a fragment of time in that other true unit, which in Rozier’s cinema is, as was suggested, the scene. It will be throughout a perseverance bordering on the absurd that, finally, the anodyne accumulation of increasingly indecipherable photogenic images builds to a difficult to categorize narrative fact, which has a lot of the characteristics of a shipwreck but also the happiness of whoever dares to film that failure head-on.

If a set of scenes make up a dramatic unit called a sequence, in Rozier that composition will then be a kind of vital unit, a procedure through which our ship captain will drop anchors in unexpected ports and lost islands to make the characters – and us – live the dream of a crazy and happy life. Maine Océan reaches the peak of this failed and happy search. Not because it is the best one, but because here we can appreciate its desire for chaos as a way of poetic progress towards happiness. Unlike other possible chaos, the chaos of this film always holds a luminosity, naivety and happiness. These three words could be the motto of this irresponsible cinema.

Is the real pursued? Is the real produced? In Rozier there is an underlying availability where the shot, like a container of a made-up world, grants several escapes, as if it were a perforated surface that allows glimpses at all times of the gleams of reality, of what precedes the shot and the film. The hippies, the fishermen, the surf instructor, the people who constantly look at the camera, the discomfort of the space, the lack of shot depth, all elements that make up something that we could call the pre-existing, and that the shot is in charge of capturing, to leave inside the ring to fight against the absurd and useless Rozierian fantasy.

But none of this disposition toward the real is related to neorealism or its derivatives. While there the pre-existing tries to be shown in an immaculate way, like a piece that the camera barely dares to look at; here, that other reality, which is not fiction, is shown to be perverted by the intention of comedy. Non-actors are far from trying to make the camera go unnoticed; rather they act badly in realistic terms, but great in Rozierian terms.

A desire for reality, close to Jean Rouch, in the sense of cinéma verité, of assuming the fact of filming as part of a fiction (or of a reality, it doesn’t matter), runs through each of his fictions/realities. But there is something else. Just as Rouch crosses the scene by making his backstage reversible, Rozier takes a different step. The script written in a weekend, succumbing to the improvisation of actors, undermining the narrative of forced twists, registering everything outside the edicts of spatial composition, letting non-actors look at the camera whenever they want, and also revealing the fact that you don’t know where the scene being filmed is going, all of this is part of not only a free and sovereign expression, but also of assuming the difficulty of filming. Cinema, for earthly beings, is a very difficult art. However, as a language throughout its history, it has behaved as if it were not. That is to say, cinema is also the act of hiding the difficulty of carrying it out. And that’s where Rozier plants his humble but outrageous flag. The way he finds to test this difficulty is to expand the shoot until it is exhausted, to stretch the narrative until it is bloodless.

His first short, Rentrée des classes, dates back to 1956. It tells the adventure of a student who disobeys the rules. If one later discovers that the episode of Cinéastes de notre temps dedicated to Jean Vigo was directed by Rozier himself (interviewing the men who participated in Zero for Conduct as children), the link between the short and the film becomes unquestionable. Likewise, Rentrée des classes responds to a genre practiced by many French filmmakers, but that disobedience portrayed by the filmmaker in discussion becomes prophetic: a modus operandi from which to channel his own relation with cinema. And probably his own relation with the world, which is the same at the end of the day.

* * * * * *

An uncomfortable silence had stalled the conversation between the filmmaker and the playwright a while ago. The filmmaker felt the ball was on his side and he lashed out:

– ‘You attribute to Pierre Richard the gift of laziness. However it seems to me that this laziness, that laissez faire, that relaxation in the face of the creative act seems to be more on Rozier’s side: in the drive to film everything, to distract himself from the great story and enjoy the small dramatic situation that just happened to him.’

– ‘Thing is that Rozier would seem to say: none of us are prepared to make to make a film, perhaps no one should prepare for such a thing. Making a film is, simply, an act of mischief.’

– ‘In this sense, Rozier practices comedy not as a narrative form but as a state from which to look at things and, fundamentally, as an avenue to let oneself go (‘To let oneself go’, repeated the playwright). In Paparazzi he is commissioned to make a documentary on the filming of Contempt and he ends up making up a portrait of the paparazzi who vainly pursue Brigitte Bardot in Capri.’

– ‘That’s right. Tragedy and drama seem to be more slaves to their narration. What film, whose story attempts drama, has succumbed to this “letting go” in the way Rozier practices comedy?’

– ‘Perhaps the intention of using Pierre Richard, the popular comedian of the time, was the strategy that Rozier found to make his manifesto visible, or to found his own myth’, concluded the playwright, thinking that if his work was not for the present, perhaps it would at least be for the future.’

– ‘To start with we should talk about the tour de force that runs through every short or feature he makes. As if Rozier did not conceive of any other narrative form.’

– ‘The last shot of Castaways is of an extra!’

– ‘It’s because there’s no possible ending in Rozier. It is unpredictable to an infuriating level.’

– ‘The last quarter of Maine Océan is with a secondary character who, in order to get to work, makes short trips on various fishing boats. There is no visible horizon and that same premise seems to be what surrounds it. The result of that bet is a seemingly infinite film, almost in a wild state. He manages to make cinema into a wild state.’

– ‘Maybe that’s his secret and cursed triumph.’

* * * * * * *

A drift in a narrative can be understood as the shifting of a story. The very definition of drift can be assumed as a drift from something. A channel that originates from a larger river achieving its own development, marked by disaster. This conception that supposes a previous story and a “new” story caused by an accident – by a whim – but, which, even so, continues its aimless path until it’s fed up, is perfectly applicable to Rozier’s dubious narrative compositions. Except for one detail: there never was a previous story, there was never a pre-history of the accident that caused this drift. There is no fracture of the story. There is not even a fracture, or a story. In any case, disaster is immanent in each shot. There is, at all times, a will to ruin. All the actions in his film are born failed, and each of his films is the story, not so much of their shipwreck but of their redemption, of their refuge in some kind of human scale. The first twist is already a false one and its perpetration is not so much the perseverance on a particular element so that in its reiteration and accumulation something else is generated, because here there is no expectation of another thing, since there was never a first thing to begin with. In some ways, it is a destroyer of developments. Not only is the punchline taken away from the gag, but also any possibly of progress, reaction, modulation of the plot, or peripety. There is in his films an abyss called the present which swallows any type of inflection, generating irrecoverable plateaus. There, we imagine, his enormous talent for producing formal modulations through montage is born. The montage as a place for manufacturing musical figures, like concrete music with cinematographic materials. He seems more like the John Cage who put on television shows than any European comedian.

* * * * * * * *

The filmmaker:

– ‘A filmmaker does not necessarily film what he experiences. But a filmmaker does live as he films and, mainly, films as he lives. The system of tastes, references and traditions inevitably mixes with his cinematic personality and his present. As if he couldn’t conceive of doing it any other way, Rozier films in a state of happiness and, therefore, the happy events become a movie.’

And the playwright:

– ‘Could this be the reason why he filmed so little?’

* * * * * * * * *

Perhaps Rozier’s cinema reveals the mere pleasure of filming for the sake of filming, and that is why it is impossible to guess where each of his films is going, or when they will end. Their narratives do not obey any known parameter: they begin at some point, they end at some other point. However, in the end, the viewer is left with the impression of having seen an adventure. This total chaos, which implies that the story is carried by one character then by another and then by others, that there is no geographical center (except Du coté d’ Orouët) that contains the story but rather that the story can move continuously without falling into the road movie genre or anything like that; that is, that there is no recognizable axis in any of the films, proves that an adventure does not require antagonists, monolithic wills nor ulterior objectives. Adventure, Rozier teaches us, is consolidated to the extent that the scene, that is, the editing, returns some shreds of what has happened there, beyond fiction, beyond fantasy, beyond that army of characters who seem ontologically oriented towards disaster, as a testimony of something that undoubtedly happened in front of the camera – and more probably behind it – and which has been happily captured and reconstructed in the editing room. It seems that this was enough to get closer to what we call reality. Nothing more, nothing less.

* * * * * * * * * *

– ‘What I believe is what the present generally recovers from that modernity are its programmatic aspects. Those aspects of which Rozier always escapes from.’

– ‘I don’t understand you.’

– ‘That these modern traces in contemporary cinema generate forms that now have their own pedagogy carved into them. Today forms are composed so that in one way or another they expose their own explanation. They are images that already contain their epigraph, their relationship with the world. Do you understand?’

– ‘No.’

– ‘Even in the biggest formal abysses that are conceived in the present, the gesture comes forward and explains what is to come in formal terms. The form has become discourse. Abstraction has been eclipsed by intelligence. The image confirms the idea. Who dares today not to be understood, to make a comedy without jokes, to make a film that escapes the categories of “good,” “bad,” “weak,” “interesting,” or any other typographical screech that the editor of the magazine suggests?’

– ‘I don’t follow you.’

– ‘I don’t care.’

– ‘You’re an idiot.’

– ‘And with great honor.’

“Elogio de un náufrago: Jacques Rozier” was originally published in the magazine Revista de cine, No.8, November 2021”

Translation by Jhon Hernandez and Jaime Grijalba. Thanks to Diego for his help with the translation. Thanks to Alejo Moguillansky for providing the original Spanish text.