Dry Ground Burning (Adirley Queirós + Joana Pimenta, 2022)

Writing and Programming from Latin America

by Victor Guimarães

“Don’t forget I come from the tropics.” The title of a 1945 bronze sculpture by Brazilian artist Maria Martins was a way of reacting against the capture of her art by a universalist criticism that stated that her work had detached itself from its tropical roots and that, therefore, after this conversion, could finally be considered at the same hierarchical level as of the great names in sculpture of the 20th century. Martins’ provocation helps us reevaluate, in these times of transnationalization, the ideas of an important text by Beatriz Sarlo, published in 1997. In that essay, Sarlo reflected on her participation in evaluation committees for films alongside European and North American colleagues: “Everything seems to indicate that Latin Americans must produce objects suitable for cultural analysis, while Others (basically Europeans) have the right to produce objects suitable for art criticism.” Apparently, the two authors point towards opposite paths: Martins resists the forced universalization of her art by claiming her place as a Latin American; Sarlo resists the exoticization and sociologization of Latin American art by claiming participation in a common ground for the evaluation of art in general. How can we think of these two positions as a productive dialectical tension in the face of the European circulation of Latin American cinema today? How to resist the sociologization and exoticization of Latin American cinema still practiced today by European festivals, without necessarily resorting to a universalist vocabulary of art criticism? How can we point towards a Latin American perspective, without transforming it into a claim outside of art, as if it were merely a matter of cultural studies? Finally, how can we vindicate the particular traditions of formal analysis of Latin American cinema to evaluate contemporary cinema in general?

This essay is based in part on my critical production over the last few years, and on some personal experiences as a programmer and jury member at international festivals. A first version of this text was presented as a conference in April of 2022 at the symposium, “Festivals et dynamiques cinématographiques transnationales,” held in Toulouse, France. The rewriting of the text took into account the responses of other researchers to the conference given in that French city (special thanks to Gloria Pineda Moncada, Amanda Rueda, Aida Vallejo and María Paz Peirano), as well as my experience in Toulouse on the jury for the documentary competition for the festival Cinélatino, which took place in parallel to the symposium.

Memory of Memory (Paula Gaitán, 2013)

Let’s start with Beatriz Sarlo. Her text from 1997, written on the eve of the new millennium, was a way of reacting to an excess of sociologization of art, provoked by the rise of cultural studies in the last decades of the 20th century. For Sarlo, “cultural studies do not solve the problems that literary criticism faces.” The problem of the literary values of a text is specific, and it cannot be resolved by a criticism that omits formal discussion.

It would seem that this discussion is exhausted today, that it raises the old distinctions between aesthetics and politics, but all it takes is to read one of the most influential texts of film criticism of the last few years, the manifesto “For a New Cinephilia” by Girish Shambu, to see that the question comes back today with renewed strength. Shambu writes:

“In film culture, value flows from pleasure, and since the old cinephilia privileges aesthetic pleasure, it has long been the key criterion of value for films. For the new cinephilia, with its expansive notion of pleasure and value, films that center the lives, subjectivities, experiences and worlds of marginalized people automatically become valuable.”

In the first place, it would be enough to go back to Sarlo’s text to find a powerful answer – and twenty years earlier – to Shambu’s text. Sarlo says: “To enter this debate, free of a moralizing bad faith, we should openly recognize that literature is valuable not because all texts are equal, nor because all of them can be explained culturally (…) Something always is left behind when we explain literary texts socially, and that something is crucial (…) To phrase it another way: men and women are equal; but texts are not. The equality of people is a necessary presumption (it is the conceptual basis of democratic liberalism). The equality of texts is equivalent to the suppression of those qualities which make them valuable.”

Mars One (Gabriel Martins, 2022)

There is no automatism in criticism. If there were, it would be impossible to distinguish between a film like Mars One by Gabriel Martins and an advertisement for a bank which featured a black family as its protagonist. At a certain point in her text, Sarlo makes a series of comparisons – between a crude political film and the cinema of Raúl Ruiz and Hugo Santiago, between a Brazilian music video on MTV and Caetano Veloso – to say that if we do not understand the distinctions between the two poles of comparison we would be mistaken. She writes: “If we do not perceive a difference between Silvina Ocampo and Laura Esquivel, we would be mistaken: in all cases, there is a formal and semantic difference that must be discerned through perspectives that are not always present in cultural studies.” In the comparison between the two writers, Sarlo recalls that, in Esquivel’s ideas about women, for example, there are a series of “politically correct” positions, but that there is a “plus” in Ocampo which is completely absent in Laura Esquivel. “Art has to do with this plus. And the social significance of a work of art, in a historical perspective, depends on this plus.” That plus, that “something,” is the aesthetic value of art, which cannot be automatic, which does not derive from the social experiences portrayed or from the social subjects that appear in the work, nor is it based on the political correctness of its authors. This “something” – which Sarlo insists on defining in a vague and imprecise way, since there would be no way to define it any other way without running the risk of assuming a totalizing and canonical position – is the heart of critical work.

But there is a more serious problem today. In many of the European film festivals, Shambu’s idea of automatism has given way – and has become an alibi – to the massive programming of Latin American films that speak the [filmic] language of contemporary Europe very well, films that portray marginalized experiences and worlds, but do so in a language that is totally appealing to European bourgeois audiences. With very rare exceptions, there is not the slightest hint of a violence, a misunderstanding, or a discomfort in the relationship between the most celebrated Latin American films at European festivals, the audiences of those festivals, and the hegemony of European criticism.

Here I will bring back something I wrote about Gabriel and the Mountain, a film by Felipe Gamarano Barbosa that won two awards at La Semaine de la Critique at Cannes in 2017, and was highly celebrated in France. The story is that of a rich white kid who decides to take a long journey through Africa before pursuing a doctorate in the United States, and ends up dead trying to climb a mountain against the instructions of the local guides. What could’ve been a truly disturbing dive into the autofiction of this kid who fancies himself some sort of hero to the African people because he gives away some dollars to his local hosts while going on safaris and mountain climbing and stupidly ends up dead is actually a pleasant tribute made by his dear friend (the film’s director), who does not let the contradictions of the protagonist interfere with the imperturbable sweetness of the story.

Gabriel and the Mountain (Fellipe Barbosa, 2017)

The liberal mechanics of the film – with its checks and balances, its apparent distributive justice, its well-thought-out balance between documentary and fiction – even if they are not capable of embarking, through excessive modesty, on the self-destructive obstinacy of the protagonist, neither can they hide what is, through poorly concealed shamelessness, the other name of Gabriel’s venture: a sophisticated and self-indulgent version of the colonial enterprise. In constant remembrance of the African characters who occasionally take over the soundtrack, Gabriel’s self-aggrandizement becomes the film’s remarkable self-indulgence: at one point, one of the men who had crossed paths with Gabriel in Africa begins to repeat the speech of friendly coexistence, and ends by thanking the film, saying that the presence of the filmmaking team there is very important, because it’s as if “Gabriel had returned.” The entire construction of the secondary characters in the voiceover – which always points to a relationship free of contradictions – reveals its double function: to forcefully sweeten the character’s trajectory (rejecting the conflicts on display) and, on the other hand, provide the film with the credentials of legitimacy.

The problems of Gabriel and the Mountain are not obvious. The solid protective shield which formed around the film among French critics is proof enough of its triumph. I quote Ariel Schweitzer in Cahiers du Cinéma no. 735: ““un hommage perturbant et sincère à l’ami disparu” (“a disturbing and sincere homage to the missing friend.”) Or Jacques Mandelbaum in Le Monde: “revisite amère du film classique d’explorateur [où le] dispositif ménage une rencontre fertile entre la fiction et le documentaire” (“a bitter revision of the classic explorer’s film [where the] device provides a fertile encounter between fiction and documentary.) The work to reconstruct Gabriel Buchmann’s last days is meticulous, from the preparation of the actors to the costumes. The script is well-elaborated, it is complex. The African characters and actors have first and last names…

The enumeration here is intentional. A critic who is increasingly accustomed to the checklists of political correctness may not realize that, in most cases, only a collision with a scene can reveal the deception. It is useless to put names and surnames to the African characters if the children continue to be filmed as a bunch of jumping bugs that fill up a scene. And when one of those children occupies the frame by themselves, it is to piss in the street, in one of those shots that Latin American pornomiseria has been able to do well, for so long, and that would be destroyed by Agarrando Pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty) by Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina, back in 1977. With the difference that, four decades later, the aggressive zoom on the poor boy’s body no longer works. Just a good wide shot, to establish the ambience, like another postcard forgotten in the editing.

My text from 2017 ended like this – “There is no doubt: Gabriel and the Mountain points to a scenario that is very clear: a Brazilian cinema which has once again learned to speak the language of the new powers of world cinema quite well; which exerted its own domestication, to the point where it became perfectly palatable to European audiences; a cinema that has renounced all opacity, all intransigence, and is advancing with great strides towards a reincarnation of the parameters of the Retomada of the 1990’s [ed. the return of the national film production], paying attention to the current demands of political correctness.”

The Invisible Life (Karim Aïnouz, 2019)

In a way, this trend – a kind of revival of the Retomada of the 1990’s – would be confirmed two years later by the triumph of The Invisible Life by Karim Aïnouz in the Un Certain Regard competition at Cannes in 2019. I already wrote about that film, so I invite you to read that text. But in any case it’s interesting to see how this return of the Retomada continues to fascinate Brazilian cinema, as if that monumental effort to speak the colonial language of international arthouse cinema was an inspiration for many filmmakers.

But perhaps the clearest symptom of the European celebration of a Brazilian cinema that is pleasant, correct and well-suited to the expectations of festivals was the great retrospective dedicated to the history of Brazilian cinema at the French Cinemateque in 2015, especially regarding the programming of contemporary films. If we take the list of recent films programmed, we will see how there is a certain type of Brazilian cinema – very characteristic – that interests Europeans and that is totally different from what the best Brazilian critics consider the most outstanding and inventive of recent years. If an unsuspecting someone goes through the retrospective’s program of recent films, they will surely think that Leonardo Lacca, Gregorio Graziozi, Fábio Baldo, Cláudio Marques and Marília Hughes are the decisive filmmakers of the first half of the 2010’s in Brazilian cinema. I don’t know of a single respected critic in Brazil who places any of these names among the most outstanding examples of Brazil’s cinema in those years. A good point of comparison is perhaps the program of 10 Olhares, which mapped the same historical period (also including the years from 2015 to 2019) through the perspectives of ten Brazilian curators. Among the 71 films selected as representative of the 2010’s in Brazilian cinema, none of the filmmakers chosen by the French Cinemateque is mentioned.

Long Way Home (André Novais Oliveira, 2018)

On the other hand, if one looks at the French list, one will surely feel the weight of the absence of Paula Gaitán, Adirley Queirós, André Novais Oliveira, Lincoln Péricles or Marcelo Pedroso among those filmmakers who were programmed to represent the first half of the last decade. There is no doubt – and it is enough to pay attention to the Brazilian criticism of recent years to realize this – that these are some of the most discussed, valued and influential names when it comes to that same historical period. There is a total disconnect between what is most valued in Europe and what Brazilian critics consider most valuable, something that does not happen when we analyze the French Cinemateque list in terms of the period from 1920 to 1990. It’s as if the European programmers of a retrospective like this one knew very well how to do their homework when it comes to the cinema of the past – already duly catalogued and canonized in the country of origin, although many times ignored at the time by big festivals – but when they have to map the recent past, they can only access what has passed through the filters of the festivals of the old continent and, therefore, through the eyes of other European programmers.

But there’s a deeper reason, and it’s not just the intellectual laziness or self-sufficiency of European programmers. If Paula Gaitán, Adirley Queirós or Lincoln Péricles are not of interest to Europe, it is because they are filmmakers who invent forms. Those forms are indomitable by the language of the majority. And if those other filmmakers are the ones that matter to them, it is because they truly done the imperative job of adapting themselves to what is expected of filmmakers from here.

The case with Argentina is similar. Some of the most important contemporary Argentine filmmakers, according to the best Argentine critics – Raúl Perrone, Gustavo Fontán or José Celestino Campusano – do not achieve prominence in the big festivals, and do not resonate with European critics. In general, there is a brutal disconnect between what is appreciated at European festivals and what critics and curators from Latin American countries say about their filmmakers.

But it has not always been like this. When Black God, White Devil (Glauber Rocha) made noise at Cannes in 1964, or when Os Fuzis (Ruy Guerra) won an important prize at Berlin that same year, it was not a matter of these filmmakers adapting to an European language, but rather a formulation of a new aesthetic, with new values. As Glauber Rocha said in “The Aesthetics of Hunger,” when this new cinema gained importance at international festivals in the first half of the 1960’s: “Diplomacy demands, economists demand, politicians demand. Cinema Novo, on the international level, demanded nothing; it imposed itself by the violence of its images and sounds in twenty-two international festivals.” Even later, in 1980, when Glauber Rocha’s The Age of the Earth appeared like a hurricane in Venice, European critics reacted to the height of the event, and could not be indifferent, as noted in a precious sentence by Louis Marcorelles in Le Monde: “un film visionnaire, hors des catégories connues du cinéma occidental, qu’il soit européen ou nord-américain” (“a visionary film, outside the known categories of the cinema of the West, whether European or North American.”)

The Guns (Ruy Guerra, 1964)

These days, it is increasingly rare to find this type of gesture at festivals and in European criticism. What is sought in Latin American countries is not what can escape from the well-known categories of contemporary cinema, but precisely what fits easily into those categories. For a Brazilian or Argentine or Colombian filmmaker to be accepted into the club of laureates by the big festivals or by European critics, they have to request a license and pay a very expensive toll: work within the known categories, speak the language they want to hear. More and more films from these countries are desired in order to meet the diversity quotas at festivals, but only those that do not threaten the idea that these same festivals have of what cinema is.

An additional problem is that the big festivals have become narcissistic industries, which, in a feedback loop, regurgitate the cinema that interests them through laboratories, market meetings and co-production systems. That is to say, they not only value a certain type of cinema in the present, but rather they prefigure future films, which tend to reflect hit formulas. As José Celestino Campusano said in an interview with Chilean magazine La Fuga: “the festivals of the First World, such as Toronto, Cannes, Venice, Berlin, are organisms of audiovisual control, because they authorize script clinics, co-production spaces, etc., but only for those who attend to their principles.”

Beatriz Sarlo already warned about this in her text, when she tells a revealing anecdote. I will quote her: ” Whenever I was part of commissions, along with European and American colleagues, whose task was to judge videos and films, we found it difficult to establish a common ground on which to make decisions: They, the non-Latin Americans, looked at Latin American films with sociological eyes, highlighting their social or political merits and ignoring their discursive problems. I was inclined to judge them from an aesthetic perspective, putting their social and political impact in a subordinate place. They behaved like cultural analysists (and sometimes like anthropologists), while I adopted the perspective of art criticism. Everything seems to indicate that we Latin Americans must produce objects suitable for cultural analysis, while Others (basically Europeans) have the right to produce objects suitable for art criticism. The same could be said about women or of the popular sectors: cultural objects are what’s expected of them and, of white men, art. This is a perspective that’s racist, even when it is adopted by people who claim to be alongside the international left. But that racism is not something that can only be imputed to them. It is also ours. It is up to us to claim the right to the “theory of art,” to its methods of analysis.”

As can be seen, this is not only an European problem, but also ours. Today in many works by Latin American artists, a notable effort to belong to the values of what is appreciated in Europe is revealed. But Sarlo’s assertion – that we claim the right to the theory of art – while extremely important seems insufficient in the face today’s problems. We must claim our belonging to the methods of analysis of the theory of art, yes, and that is an important first step. but the theory of art in Latin America is not the same as in Europe.

Black God, White Devil (Glauber Rocha, 1964)

A different perspective is what we find in the trajectory of Maria Martins. The Brazilian sculptor, at the height of her appreciation by European and North American art institutions in the mid-1940’s, after being accepted as part of the modernist canon due to the universal qualities of her work, she sculpted an anthropomorphic bronze, both sensual and aggressive, sinuous and violent, and provocatively names it: “Don’t forget I come from the tropics.” Around the same time, in 1946, she wrote and engraved in metal a handwritten poem titled “Explanation,” which reads: “I know that my Goddesses and I know that my Monsters will always appear to you as sensuous and barbaric / I know that you would like to see in my hands reign the immutable measure of eternal links / You forget

that I come from the tropics, and from much farther away.”

That violent address in the discourse toward European and North American audiences, so similar in tone and argument to what Glauber Rocha would do twenty years later when delivering “The Aesthetics of Hunger” in Pesaro, is very valuable for our argument here. What Maria Martins does is claim that the strength of her art, the values that make her great, are not the same as those of European modernity. When everyone, even a Brazilian critic like Mário Pedrosa, expects from her a step toward a stoic and balanced formal abstraction, she immerses herself in the Amazon and claims that hybrid space between abstraction and figurativeness, and decides not to abandon – but rather to affirm – the tropical and mythological roots of her art, which are not incompatible with modernity. If in the 1940’s, the art of the tropics was seen as a kind of joyful exoticism, and modern European art, on the contrary, moves toward a refined abstraction, Martins claims her own path: modern, yes, but sensual and aggressive; tropical, yes, but in a monstrous and violent way.

On the one hand, we have to do the work – as Beatriz Sarlo does – to claim that we, those of us who come from Latin America, are also capable of making works that can be included in the same pantheon of Europeans. It must be said that the cinema of Raúl Ruiz or Julio Bressane is fully comparable to the greatness of Manoel de Oliveira or Jacques Rivette, just as the greatness of Clarice Lispector’s writing is comparable to that of Maria Gabriela Llansol. But, on the other hand, it is necessary to advance along the theoretical path pointed out by Maria Martins, in the sense that the cinema of Ruiz and Bressane are equally great, but not according to the same categories from which we evaluate the cinema of Oliveira or Rivette. The forced Frenchification of Ruiz’s cinema – to the point that symptomatically, the French Cinemateque premieres the restoration of one of his earliest Chilean films and names the filmmaker with the “o” between the “r” and the “u” (Raoul) by which the spelling of his name has been known in France, a non-existent “o” in the very credits of the film – this submission of Ruiz’s cinema to European cinematographic values does not reveal what is most powerful in a film like On Top of the Whale (1982). Reading this film from Latin America is to place its gesture in one of the most important artistic battles in the history of Latin American cinema. The value of On Top of the Whale does not reside only in the sophistication of its narrative labyrinth or in the expressiveness of its visual textures, but rather in its absolute destruction of colonial rationality. Glauber Rocha had already died when this film was released, but he would surely recognize in it one of the most important points of his “Aesthetics of Dreams” I quote Glauber: “revolution has to be impossible for dominant reason to comprehend, so much so that it denies and devours itself when faced with the impossibility of understanding,” in what could be a beautiful synopsis of Ruiz’s film.

Dialogues of Exiles (Raúl Ruiz, 1975)

To write from Latin America, to program from Latin America, is to return to the scene in Dialogues of Exiles by Raúl Ruiz, in which the character played by Argentine filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky initially addresses in French two well-intentioned bourgeois women who want to help the Latin American exiles, and then later sits down and starts speaking in Spanish: “in the first place, the most typical experiences of modern man, a certain impermanence, a certain transculturation, a certain passing through things, were made by Latin Americans, I am not saying by all of the Third World, but by Latin Americans, long before all the Europeans. Because deep down we are all mestizos. And, secondly, all those things that Latin Americans most envy in Europe are those that Europe today is trying to get rid of with great difficulty. I am referring to certain forms of overdevelopment, of technological advancement. It is a situation that could be compared to what perhaps you, ma’am, felt years ago, when you were poor, when you saw something in the Balenciaga window that you liked and that you could not buy. And today, when you can buy it, you realize that it’s gone out of style.”

Writing from Latin America, programming from Latin America for us is, on the one hand, recognizing and recovering our old strength, which resides in having invented our own version of modernity. On the other hand, writing from Latin America, programming from Latin America, is rejecting the mirages from that Balenciaga window. To break the glass, one more time.

Writing from Latin America is to claim, against the decadent values of the hegemonic European film criticism – so imitated in Latin America – a link to what is most vigorous in our theory of cinema. This means linking, for example, the work on digital precariousness by the Portuguese filmmaker Pedro Costa to the Latin American theory according to which the strength of our cinema would be affirmed by the incorporation of material precariousness as an aesthetic value, which would imply an attack on the colonial focus on technical perfection. Something that begins with the use of expired film and the maintenance of a failed soundtrack in Tire Dié by the Argentine filmmaker Fernando Birri, continues in the handmade editing by the Uruguayan Mario Handler of Carlos: Film Portrait of a Montevideo Panhandler, and will culminate, theoretically, in the Aesthetics of Hunger of Glauber and in the imperfect cinema of the Cuban Julio García Espinosa. We must rediscover those clandestine bridges, as the master José Carlos Avellar would say. We have to read cinema – even the European one – according to the original values elaborated by the Latin American cinematographic tradition.

Agarrando pueblo (Luis Ospina + Carlos Mayolo, 1977)

Writing from Latin America, programming from Latin America, is fighting against the European and North American acclaim of a film like Roma, by Alfonso Cuarón, a kind of revised pornomiseria. Because we have seen Agarrando pueblo by Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo, because we have read their manifesto distributed in Paris by the time of that film’s release, we cannot accept that Roma is considered one of the best Latin American films of recent years. If in 1977 Ospina and Mayolo denounced that “misery was being presented as one more spectacle, where the spectator could wash away their bad conscience, and be moved and calm down,” the criticism that accepts the consecration of Roma – even the Latin American criticism that imitates the European one – has forgotten the lesson and must be awakened once more.

We must not forget the past and repeat the same mistakes in the present, but we must also be attentive to the inventions that are happening right now. As long as we continue to allow the categories of analysis to be produced by Europeans and North Americans, as long as we don’t write and program from here, the cinema of the most important Brazilian filmmaker of today, Adirley Queirós – who is just beginning to be known in France, a symptom of a monumental delay of the critics and of the French festivals that would’ve not occurred in the 1960’s – will continue to be valued (if it is) only for its denunciation of the social situation in Brazil and for its political opposition to the current government, and not for its intricate formal elaboration, for its extraordinary elaboration of a method and a poetics on the threshold between fiction and documentary, nor for its vigorous and original theoretical formulation of what he calls “the ethnography of fiction.”

In a certain way, Argentine criticism offers us a possible path. If today filmmakers like Lucrecia Martel, Lisandro Alonso or Mariano Llinás have become inescapable names in contemporary cinema – although others who are equally important continue to be ignored – this is due to the fact that the critical and curatorial work carried out in Argentina knew how to invent criteria, forge local values capable of confronting European ignorance.

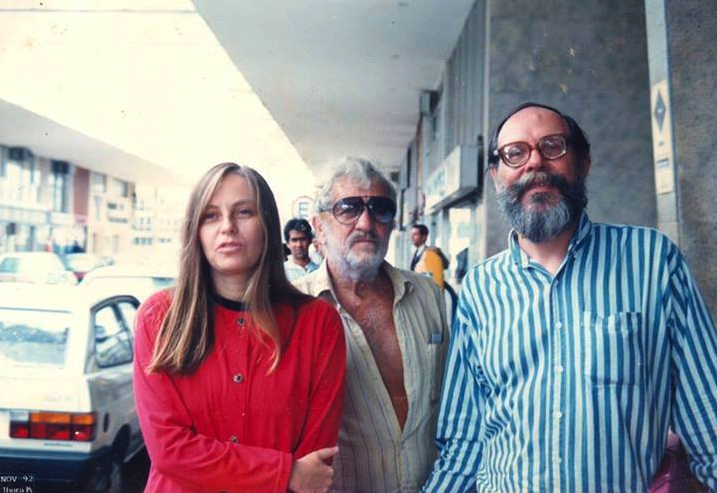

Paula Gaitán, Ozualdo Candeias and Carlos Reichenbach at Festival de Brasília do Cinema Brasileiro in 1992

There is an immense amount of work to be done to develop critical and curatorial advocacy that can influence the international arena today. If the cinema of Rogério Sganzerla or that of Ozualdo Candeias today occupies an important space in international cinephilia – although European festivals dedicated retrospectives to them much too late – it is because the work of critics like Jairo Ferreira, Jean-Claude Bernardet and José Carlos Avellar became so emphatic that it made them inescapable. But in relation to today’s filmmakers, we cannot wait for European benevolence for a future reassessment. The modus operandi of most European programmers is to dedicate retrospectives that “discover” authors that they themselves have ignored for their festivals decades ago. But when the 2035 Rotterdam festival finally decides to dedicate a retrospective to Paula Gaitán or Lincoln Péricles, it may be too late.

As Solanas and Getino said about the passage to a Third Cinema, it is necessary to not stop taking advantage of any of the loopholes that the hegemonic systems of valuation still allow; which, in our case, from the point of view of programming, means influencing curation, competing for spaces in the international arena. On the other hand, it is necessary to forge local Latin American alliances that are capable of confronting the privileged categories of the great European festivals. To create, right here, critical and curatorial spaces that allow us to give visibility to the most intransigent cinematographic gestures made between us.

A recent text by Fábio Andrade moves in the same direction. Critically examining a supposed “post-colonial situation” of Brazilian cinema – propelled by the euphoria over Bacurau and The Invisible Life‘s awards at Cannes – Andrade invites us to work on forging our own values and developing criteria for a Brazilian cinema that “has experienced a moment of great aesthetic and political explosion” in recent years, but that does not find resonance in international hegemonic circuits. Andrade writes: “A colonial history: when the appreciation criteria are forged in the image of foreign cinemas, the new questions, which are asked in their own lexicon (not detached from the world, but carrying with it the inexorability of experience), fall on deaf ears. Given the very conditions of circulation of small and medium-sized films today – which are almost always inaccessible once the windows of commercial exploitation are closed, sabotaging their own historical future – the cinema made today will find even greater difficulties for future reevaluation, increasing the responsibility for blunt affirmations in the present.”

As long as this colonial situation remains, filmmakers like Ana Pi, Getúlio Ribeiro, Clara Chroma, Tavinho Teixeira, Glenda Nicácio and Ary Rosa, or collectives like Surto & Deslumbramento, Anarca Filmes and Chorumex, will continue to be, for Europeans, illustrious unknowns. And twenty years from now, the same programmers who reject these films at the festivals where they work will do retrospectives to “reveal” them to the European public twenty years too late.

Our job is to affirm, over and over again, in always renewed and imaginative ways, in all the spaces where it is possible, that there is a Light in the Tropics – a light of its own, and ours – to vindicate the title of the monumental film by Paula Gaitán, a film that works in a field alien to all known categories of contemporary cinema, and whose strength is comparable to what Marcorelles wrote about The Age of the Earth in 1980, but whose international trajectory is ridiculous when compared to its greatness. These are the filmmakers who continue their silent work, regardless of the values appreciated in the big festivals. These are the ones who, to paraphrase the title of Maria Martins’ bronze, have not forgotten that they come from the tropics (and from much further away).

The Age of the Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1980)

“Escribir y Programar Desde Latinoamérica” was originally published in Con los ojos Abiertos on September, 10th, 2022. Original text by Victor Guimarães.

Translation by Jhon Hernandez. Thanks to Victor Guimarães and Roger Koza for permission to publish this translation.

Lots of food for thought and names to search out here, but it’s depressing to see how Latin American films need to be lauded at those European festivals to get even a marginal U.S. arthouse/streaming release. DRY GROUND BURNING is the only title by one of the contemporary Brazilian directors mentioned here to make it into U.S. theaters.

LikeLike

Hi, Steve

Sorry for the late response. Yes, it’s a shame. There’s a belief that if a Latin American film isn’t in one of the big European fests, then it doesn’t exist. As this text shows, there’s a vibrant filmmaking scene in these countries that’s not traveling much farther than its own borders (from a distance, the festival ecosystem in South America is quite interesting). In the United States, there are many festivals dedicated to Latin American cinema that do bring in works that we would consider in the B-Tier but these don’t get very much attention as they’re pretty local events (aside from Neighboring Scenes which weirdly didn’t have a 2023 edition). But those festivals won’t go anywhere near a Campusano or a Fontan mentioned in this piece, let alone some of the more offbeat choices. I am not personally familiar with a lot of the directors that Victor talks about in this piece, but the polemical nature of the piece excited us and we thought it would be a good way to introduce some of our upcoming texts. Thanks again for your comment!

LikeLike

Since Lincoln Pericles was praised so highly in this essay, I wanted to share this link to his YouTube page: https://www.youtube.com/@lincolnpericles. (Several shorts are subtitled in English.)

LikeLike