Carmen Leroi’s first two short films feature two characters named Elsa. In one film she is a young woman in her late 20s, and in another she is a woman in her 40s. In the first film, Les belles portes, her brother appears and disappears over the course of 15 minutes, and in the second, Pour Elsa, the brother has long disappeared and is just a picture in a frame. At first, we begin to suspect there’s a family history behind these images, some private mythology being explored and opened up in the realm of fiction. But the films go elsewhere, tease us with hidden mysteries… What is going on in the cinema of this young French writer and director, Carmen Leroi?

Elsa

Carmen Leroi took her first steps in the cinema world with her association with the Entrevues Belfort film festival (her debut short, Les belles portes played there in 2018) and then later by joining Bathysphere Productions, responsible for the majority of Guillaume Brac’s productions in recent years, as well as the work of critic-turned-filmmakers like Laura Tuillier and Louis Séguin, friends of the director.

But her first film, Les belles portes, is a true independent production where she acts in front of the camera as the main character, Elsa; her friend, critic and programmer, Vincent Poli, plays her brother; and her father shows up for a brief scene. Behind the scenes, she acts as her own cinematographer with some assistance from Poli.

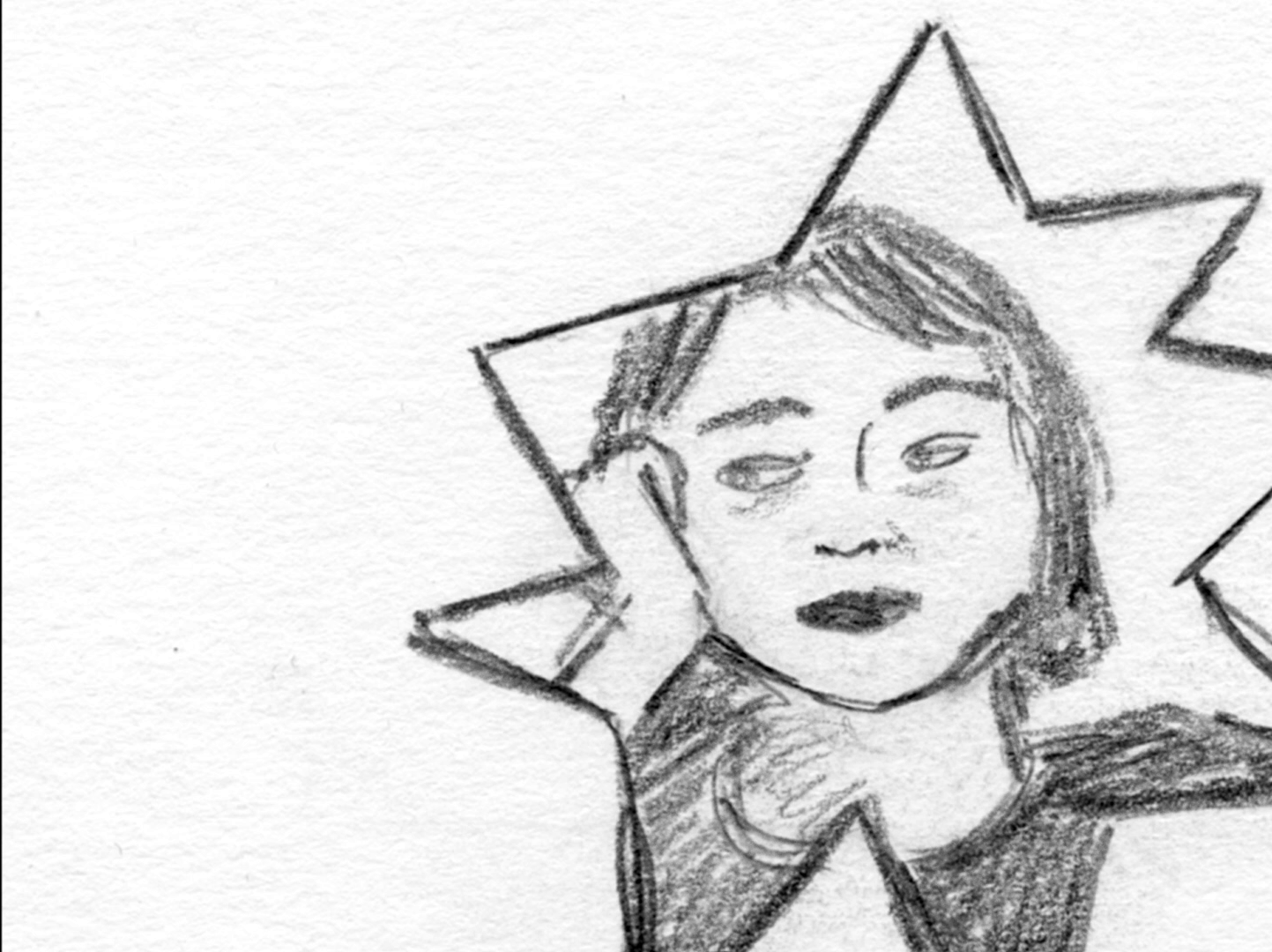

The very first shot looks up at an apartment window. The following shots will take us inside the apartment, getting closer and closer to a subject, Elsa, before backing away. Before any of the major characters are fully seen, there is a shot of two picture frames, brother and sister side by side. When we do finally see Elsa, it is a shot of her back, facing away from the camera. And then an over-the-shoulder shot as she looks through some drawings. It is somewhat perverse that during the first 3 minutes we almost never see her face. It’s only later, after her brother has been glimpsed from a distance, that we finally get a clear look at our supposed main character in a shot where the two watch an old film in a dark room. I struggle to interpret this strategy. Is it confidence? Or a reticence? Narrative information is delivered first through a shot of a piece of paper stuck to a wall, and then a shot of a window of a moving train, as text messages are overlaid on the image. When the characters are finally united together in a shot, around the 3 minute mark, we understand a bit of the family dynamic, we understand the visual strategies that will be deployed, and we understand the rhythm of the editing.

The confidence lies in the ability to cut on a suggestion, to move forward without lingering, to map a small world out of fragments. In this first short, the world is indeed small. It’s made up of one apartment, a couple of shots stolen outside, and not much else. The brother has returned suddenly from China, without warning. They hang out in the apartment. He teaches her about the meanings of some Chinese characters. She cuts his hair. She draws him. They watch films on tv. Each morning Elsa approaches the door to his room, knocks on it, and then opens to see if he’s there, as if she is anticipating his absence.

What is this strange film about? The brother returns, the brother leaves, then the father comes back, and somehow the cat is always there. There is a mystery at the heart of it that seems slightly outside our grasp. We glimpse the brother for a brief moment in the final shots of the credits, going off again on another journey, to parts unknown. But the impulse behind both his arrival and his departure are complete blanks. Elsa is left alone with her father. And we know almost nothing about her (in the film, she appears to draw some sort of storyboards). But what Leroi has filmed is the act of leaving, in the form of a question. The absence of an explanation is what we take away, the phantom next shot that is made up in our mind to bring reason…

As I watched Pour Elsa I began to spin elaborate theories. This Elsa is the same Elsa 20 years later, her brother has also disappeared, and she will disappear in the same way. Vincent Poli is cast in a small part, two brief shots, where he knocks on Elsa’s door, looking for her. Is this Elsa’s brother returning to her, without aging? He denies being related to her, but his exact relationship to her is never explained. What is going on here?

The world is bigger. Two years after the debut of her first short, we can already see an expansion in resources and in ambition. If her first film sequesters itself in a small apartment, then this one opens up the world. The same visual strategy opens the film. We start from the outside world to the inside of the apartment. But in Les belles portes the shot was focused on the outside of the apartment window. In Pour Elsa, we see a cityscape, a skyline, smokestacks in the air, before finally getting closer to an apartment building and its many balconies. And once we’re inside the apartment building and we meet Elsa, we also meet her neighbors, a young girl named Alice (this will be her story in the end), the property manager who’s always sweeping nearby, a piano teacher, etc.

When Elsa invites Alice to use the piano in her apartment the focus switches from the older woman to the young girl. We follow Alice as she plays with her friends outside and practices “Für Elise” on the piano. She learns a little about Elsa (her brother disappeared, just like that) and feeds her dog while she’s out.

Elsa disappears from the film without any fuss, just like the brother in Les belles portes. There’s no announcement, no explanation behind her departure. Alice realizes something is wrong when she realizes that the coffee on top of the piano smells weird and has mold. The film then follows Alice and her mother as they try to reach out to people who might know her and who might know what happened to her.

Two films, two disappearances. Leroi’s first two shorts track the ways in which people enter and leave our lives, often without reason. They’re not exactly ghosts, but they fade away just the same. In Pour Elsa the disappearance is navigated through the eyes of a young girl who does not quite seem to register the fact that a life might have ended (her cousin suggests “maybe she’s dead?” and the camera pans to Alice quickly in a clumsy and lovely handheld shot, and she simply laughs). The disappearance in Les belles portes is that of a young man who seems to be traveling without much thought. When he leaves without saying anything, it could be interpreted as the wanderlust of the young. But the disappearance in Pour elsa is that of middle age, an apartment full of family histories, regrets, obligations. Our minds turn toward death. The beauty in Leroi’s film is in the dedication – the film is for Elsa, to remember her, maybe to show her that her dog is being cared for, that her piano is being played lovingly and with care, that the wind will keep blowing through the trees, that the sun will continue to shine, and that her city will retain its beauty.

No Regrets

If in her first two short films Leroi hinted at the idea of ghosts that disappear from the narrative of the films, then in her longest and most ambitious work so far, Sans regret, she commits entirely to this idea and films ghosts for the first time.

Sans regret is adapted from the short story by Lisa Tuttle, “No Regrets,” from her 1987 collection, A Spaceship Built of Stone and Other Stories. It tells the story of Miranda Ackerman, a mostly successful writer who is invited for a residency at a university in her old town, and moves back into the same house she lived in so many years ago. It moves the events of the story from Texas to Leroi’s home town of Caen; it makes Richard, the literature professor, into a film professor; and, perhaps most importantly, it softens the edges of that character by casting Emmanuel Mouret, a very unique performer who seems incapable of guile or malice.

But what exactly are the ghosts Leroi is filming? Explicitly, she films the potential lives that were possible as they play out in front of the main character, the choices not taken materializing before her eyes. Julia Faure plays Miranda Ackerman, an actress with a certain poshness, yes, but also an icy remove. There’s a haughtiness to her approach to this character which is unmistakable. When confronted with the potential life she could’ve had (a more quotidian life, centered on motherhood), she responds as if she’s being attacked for her choices – she defends the life she has, the cosmopolitan nature of Paris, the intellectual circles she runs in, all of which would’ve perhaps been impossible if she had stayed in the relationship with Richard, if she had children.

When we invoke ghosts, we invite certain associations, certain images… This house where she stays does contain mysteries, certain apparitions and noises which belong to the supernatural. One morning she goes to the kitchen to see Richard there making coffee, and then a cut makes him disappear. She sees a young girl running past a hallway. Suddenly she begins to dread the thought of staying in this home, to face the embodiment of her choices (or rather the choices not taken), to face the daughter she never had, to face another life…

In Sans regret, Carmen Leroi fulfills the promise of her early shorts, leaping from the neighborhood portrait to a psychological nightmare scenario, melancholy and horrible at equal ends. Because the ghosts are not contained within the house. There is a young student who acts as a chaperone, and her relationship with her boyfriend plays out before Miranda, an echo of her past. There’s even a remarkable visualization of the film’s main idea later on where we see that for this character multiple lives are possible, depending on the choices she makes. And Leroi, via Mouret’s film professor, shows a scene from Satyajit Ray’s The Coward which recalls her earlier relationship as well.

What I find most interesting is the lack of judgment on the part of the director. There is compassion here toward this character. Leroi honors Miranda’s ambition and her choices, while presenting her with the comforting embrace of missed opportunities (how boring it would be without regrets). Julia Faure is magnificent in her struggle, against Richard and the image of his family life (heard, but not seen), against the economy of her life which makes it so she can’t live off her writing (she is very blunt about this to the student), against her own weakness (she never gives in, until she does in the film’s final shot).

There’s something to be said with working with a movie star. In Faure, Leroi has found a perfect avenue for the films’ poetics – the contradictions, the violence, at the film’s center play out across Faure’s face. And the contrast against Mouret is crucial. Here is Mouret who has for 20 years acted as the epitome of a certain romantic clumsiness. Even as he suggests theories to Miranda, you can never detect any malice or ill will (he’s a family man now). In the short story, there’s a running inner monologue that accuses his character of orchestrating all the little humiliations of her residence, but you could never really say that of Mouret. It’s hard to imagine Mouret showing that scene from The Coward knowing that Miranda is there, antagonistically, which is closer to the conception of the character of the story. By staging these two actors together in the frame, two completely opposed styles of acting, she makes Miranda’s inner agony more pronounced, more affected, more baroque. It prepares us for the film’s final leap, from the suggestion of an alternate world of ghosts, to our full acceptance of them.

Perhaps we can term this period the Mouret years. After casting him in a supporting role in Sans Regret, Leroi partnered with him to write and direct a short called La Réputation. Leroi steps in front of the camera to play a film director who’s editing her film, a type of suspense film, and is working on the sound editing. She then hears that her sound editor has a notorious reputation as a lothario, seducing multiple women on the sets where he works. The question is then: why isn’t he trying to seduce me?

The scenario belongs more to the Mouret universe, closer to his short works like Tout le monde a raison, where the female protagonist is absolutely convinced that she can tell when a man is lying to her and her boyfriend resolves to test this hypothesis. Everything belongs to the imaginary. There’s less mystery (no ghosts, no other lives) but rather the precision of a train of thought, spoken out loud, followed to its conclusion. Desire and love are Mouret’s great subjects – he tests out ideas, experiments, theories and uses a variety of performers to stage his pirouettes. Let’s say that in the last 15 or so years he’s moved toward a crystallization of his concerns – that is, his characters only talk about desire, about affairs, about relationships, there are few concerns outside of this. There’s very rarely an everyday texture to his films. So in Diary of a Fleeting Affair, for example, Vincent Macaigne is able to go on weekend trips with his lover because his wife has the kids and has gone away for the weekend, the reality of holding down a job doesn’t matter. And even in the supposedly middle-class world of the characters of Mouret’s latest feature, co-written with Leroi, Three Friends (almost all of whom are teachers), the children of the characters are there one second and then later go away when the plot doesn’t require them to be present. I say all of this to bring up that when Carmen Leroi steps in front of the camera in the role of a young filmmaker, she brings with her a world that’s more concerned with work, with the everyday texture of a working life (even if it’s that of the director). The imaginary and desire are part of the film, of course, but they’re subsumed to a discussion about mores in the workplace, about how desire infiltrates the everyday and takes up room in our mind… Notice how many of the conversations that happen are a part of everyday domesticity – she discusses the matter with her boyfriend as they fold and put away clothes, for example. It’s a much more stripped down production, shot in what looks to be Frédéric Niedermayer’s offices (a poster of Brisseau’s À l’aventure hangs on the wall), and the talk feels more concrete, more direct. In La Réputation, we can say that she grounds some of Mouret’s more whimsical turns, that she brings an everyday touch to those same conversations of desire, an approach that questions them while at the same time indulging them, that might have been staged differently with another actress (one who might’ve been more eager to play along with the role like his previous actors). In essence, the friction between them, the desire to stage this game but in a different register, is what makes the film worthwhile.

In the case of their feature collaboration, Three Friends, I often wondered if Mouret brought on Leroi on to help with the Macaigne sections (the voiceover in particular). Because the perspective is one that’s removed from the narrative, it’s a ghostly one we must say (the film is narrated by Macaigne’s character who passes away early on), but it’s wise, full of love and regret. It’s this gesture that makes the film stand out, and if the rest of the narrative strands are interesting enough, it’s the Macaigne sequences that make the film great. It’s a bit of a variation on those same ghosts that Leroi staged in Sans regret, but instead of another possible life appearing before the main character, it’s an entire other plane of existence from where one character sees the events of the movie. Mouret has never come close to staging scenes like this (maybe in certain parts near the end of Caprice…) and India Hair’s character is also something entirely new… This is perhaps the secret to having a career of 25 years. New collaborators allow a freshness to express itself, different facets of the worldview of the filmmaker open up, new avenues to explore. Carmen Leroi in these two collaborations has allowed something like that to happen.

The latest short film by Carmen Leroi, which premiered in the Critics Week, is called Free Drum Kit (Donne Batterie). It tells the story of a young woman who wants to give away a drum kit left behind by her ex-boyfriend. It’s important that it’s free because she wants to explicitly do something good and does not want to profit from it. It is not too far from La Réputation, where an idea took hold in the imagination of the character, an idea that intrigued them, puzzled them, excited them. And the fulfillment of this idea in the real world is part of the film’s drama. But what is new? The explosion of dialogues, analysis and rationalization from the characters that belies an eccentric spirit which abandons somewhat the controlled frames from the earlier films for a rougher handheld approach (there are even whip-pans). It’s a film closer to the spirit of the street, where there’s a certain chaos, where there are confrontations between individuals but also random meetings by chance. The comic nature of this young woman’s desire to do a good deed is accompanied by a certain mania, by a certain ridiculousness – at what point do we give up our schemes and just accept defeat? To give away this drum kit will require a discussion on if you should sell it or give it for free, a system of probability to decide who will get it, a review of the potential new owner’s messages and their sincerity, and then to reconcile all of this with the coincidences of life (perhaps the drum kit should actually go a new romantic interest). The film respects the quixotic nature of this character’s desire and, perhaps most movingly, how everyday life becomes a sort of game for the characters, a game based on pleasure, yes, but also morality. The comedy is in how this character’s sense of morality clash with strangers on the street who just want to buy a drum kit for their son, or the guy who is trying to make a sale. Marie Rosselet Ruiz in the main role brings a neurotic earnestness to the film and makes the bundle of contradictions at the heart of it human (and funny). In the final confrontation, she is belligerent, more than a little zany, passionate (in an entirely wrongheaded way), but she is given grace. In the final shot, the credits shot, she is given time to breathe and reflect; it’s a good drum kit, actually, and she is a good girlfriend. More than anything else, the surprise of this short reinforces the idea that with each new film a filmmaker has the opportunity to erase what has come before, to pick out a new set of clothes, to veer wildly off the path… It’s always an option.

With Free Drum Kit Carmen Leroi will have five short films over the course of seven years. And yet she has not made a feature. Leroi, in the interview we have published with her, theorized that it’s very hard to make a feature in France without an important “subject.” Does independent cinema exist in France? Because of the reliance on state funding, there’s a certain standardization to the productions, even on smaller films you will still need a certain amount of professional crew, a bigger footprint. Maybe I am uninformed, it’s possible.

I wanted to write about Carmen Leroi because she’s someone of my generation, even if from across the planet, who has steadily begun to work and make a name in the industry. It would not surprise me if in a few years she has a debut film premiere somewhere which critics will believe ‘announces’ her to the world, but there is always a path before that moment. Some combination of shorts and labs and funds that allow someone to be discovered. And it’s interesting to think about this at this stage and to take stock of their career. With this piece, we begin to track Carmen Leroi in earnest. We are eager for her next films.

Read our interview with Carmen Leroi here

1 comment