How did you get into film directing?

I started out mainly interested in music, but as I had no aptitude for it, I switched to literature. I wrote two or three stories when I was young, but I had no aptitude for literature. It tired me a lot, the blank page gave me nightmares. Like that, I also failed at literature. So I thought about painting. I had no sense of color, so I also failed at painting. By failing one, by failing the other, I arrived at direction. I may have also failed at direction, but in the meantime, I will continue along this line.

The first time I thought of making films, it was out of a passion for sports. I did a lot of mountain climbing in my youth. Around eighteen, I was a promising young mountaineer. I climbed with a famous guide, Emilio Comici, who unfortunately died in a mountain accident in 1940. In short, it was a promise I didn’t keep because, at a certain point in my life, I became afraid. But at that time, I took a lot of photos, and I was very good at taking them with lighting that suggested a certain obsession with the vertical, conducive to the expression of the bodies in the rocks. Emilio Comici was always asking me for photos because in his conferences he made projections to illustrate his technical explanations. And I started to get interested in 16mm documentaries. I studied editing and began to discover certain laws, such as repetition, and that if you repeated the same movement three times, it became obsessive. And my friend said to me: “No, you mustn’t do that, it’s a documentary, not a film.” So I discovered a few little things that began to interest me as possibilities. At the same time I had the opportunity to see avant-garde French films like Blood of a Poet and Entr’acte.

However, I’ve never made a film about the mountains. There is one story I’d like to film and it was the first thing I thought of when I had the opportunity to direct: a novel by Ramuz that I find extraordinary called La grande peur dans la montagne. In this very mountain, there’s a sense of panic and death. The producers didn’t think it was commercial. But I haven’t given up hope of making this film in the future.

After this first contact with the camera, I became more interested in films and I looked at them from a completely different point of view. I was much less interested in the story than in the story’s secret feelings, the composition of the image and the linking of shots, camera movements, questions of lighting.

Do you leave room for improvisation in the shooting of your films?

The spirit of improvisation, of which Rossellini is the true master, always forces us to make the film on the least complete, the least mature découpage possible, to give the impromptu more possibility. But the more experience I gain, the more I understand that this is very dangerous and that, on the contrary, you have to be very exact in advance on every point, except the arrangement of the shots. What I never understand when I read in a découpage are the words “tracking shot” or “close-up” or “master shot.” These subdivisions should never be read because they’re distracting: it is the scene itself which must suggest the movement to be made. You should never arrive on set already “tamed,” with everything you need to do already in your head. You have to get there with your head completely free, and then you consider the primary focus, which, depending on the scene can be the set, the ensemble, a detail, a movement, etc., except for certain scenes which were created while working on the découpage, as if we were already shooting them. This was particularly true of several scenes in Traviata ’53. If you lay out all the shots on the drawing board, literally, it becomes forced, it becomes false and, finally, it becomes conventional. We arrive at the set, start at the beginning – it’s a mistake to start at the beginning, isn’t it? – and we consider the primary focus, we execute the first moment; from the first movement, the second becomes almost a necessity, that is, you take on a rhythm of images, a theoretical rhythm that doesn’t correspond to the rhythm born of the concrete reality of shooting. This raises the question of the composition and decomposition of images, which is the point of view of, let’s say, space-time.

In a painting, the painter gives us movement in the same way as in montage, i.e., the eye comes upon one thing before all the others: the painter has given us a point of view, a particular light on things, which strikes us first. Then the eye travels and sees something else. Or, the painter has given us a totality, the eye catches this totality then travels and sees the details. This is the painter’s montage, and this movement suggests a direction that gives the painting a magnitude even beyond its material limits. Cinema, on the other hand, doesn’t need to invite the eye to determine the shot – since it does this for itself. It must do so with such precision that the eye finds precisely what it expects to see. In my opinion, a bad shot is one where the eye is looking for something, looking for a detail when it’s given the totality, or looking for the totality when it is given the detail. Good shots are those which, in movement, action, or even the expressive charge of the eyes, suggest to us the transition to the next shot. This is too difficult to pre-organize on paper, the découpage must give the fictitious construction, the project. If it is true that cinema is an expression, a language, let’s say that it is the idea of creating a certain language, it is not the language itself. When we publish the découpage of a film, we should say “the filmed découpage of a film.” It always annoys me that publishers don’t publish the découpage before the film and the découpage after. You’d see that with most directors, most good directors, there are a lot of changes between what they had planned and what they actually did. I’d like to check how many times we’ve written: “The actor smiles, happy” and then filmed the same actor with tears in his eyes. Because, while we’re shooting, we see that an expression, a position of the head, a feeling doesn’t resemble the real life of the film – which is never real life, but always an abstraction, a transformation – doesn’t resemble what we’d written. That’s why I think that, for a director, having everything pre-ordained certainly gives him a sense of assurance, but not the thrill he must always feel while he’s making these things, the thrill of discovery. To take an example, a tree is always a tree; but if, while I’m setting up the camera, I try to “catch” this tree, I discover it for the first time. I’ll say to myself: “Oh, there’s a tree.” At that moment, I’ll find the right place for the camera, I’ll find the right light, I’ll give it the essence of a tree, the expressive power of a tree, whereas if I’m prejudiced about the tree, it becomes another tree. There’s no such thing as improvisation in all this; it’s more a question of discovery.

It’s a theme that I feel very strongly about, death, in all its degrees, because all of life’s dramas are degrees on the way to the great final death. And everyone knows about death, everyone has seen it, but every time I have to film it, I try to discover it. That’s why I believe I’ve done it well. In Traviata ’53, the young girl’s death is a discovery of death. The girl isn’t there, she’s already in the closed casket – it’s being nailed shut – the guys don’t care, they’re just nailing the casket shut. Everyone has seen this, had someone close to them die, and had to close the casket. Each time, death must be discovered according to the character, the general line of what we’re looking for. In Legions of the Nile, I was looking to consider death from a historical point of view, that is, as a symphony of colors that would also reflect the metaphysical presence of death: the death of a great character must be the death of the whole. This gave me an idea of color, of position, as I was shooting. I was in the process of placing the dead man, then I said to myself: “No, that’s not it”; I moved him, and thought of the red coat, which I placed over him; then I placed the dead man’s friend with this red coat, on the other side. Finally, I build up this death piece by piece, to discover the death of a great historical figure.

Augustus arrives at Antony’s body and realizes that this is not the suicide of a desperate man, but a glorious death, the culmination of a lifetime. It’s then that he understands Antony’s greatness.

I don’t know if I succeeded in expressing everything in the scene, but I wanted to give the idea that in Augustus, at that moment, there were three feelings; and this had to be conveyed through attitude alone, because we couldn’t do a close-up of Augustus, which would have meant nothing in a scene where you have to breathe in the whole setting at once. So, in his attitudes, gestures and poses, I wanted to express three things: the hatred he felt for his adversary, admiration, and a Roman sentiment, that is, his satisfaction that a Roman had died a great Roman. And these three feelings must have been conveyed by his walk towards the dead man, his short pause, the way he turned his head towards him, without any sign of respect or greeting, but only looking at him with a certain pride, and then moving up the stairs away from him. I don’t know to what extent the goal was achieved because, as always in a film, the secret feelings that are to be communicated to the audience must not reach them with the clarity of explanation, but somehow in the unconscious. Then you can say to the audience: “Look, that means this, this and this.” If the audience responds: “Ah, that’s true, I hadn’t thought of that,” it’s a success in terms of filmic communication. The audience can discover the feeling, if it examines itself, if it discusses it.

If it is a secret feeling and you show it clearly, you can only show it as a secret, force the public to discover it.

Ah yes, I always fear being too explanatory. In Clouzot’s La Vérité, there’s a little too much truth. Clouzot, like Cayatte, explains far too much. He gives us a pure feeling. A feeling that’s explained becomes impure. The camera has an incredible, extraordinary power to see inside things. We must not externalize it. It makes me laugh a little to say that. I make cloak-and-dagger, swashbuckling adventure films, but what I’m also trying to do with this kind of film is capture some small inner truth, to suggest it to the audience, not to make declarations of principle. With films, there’s always the risk of moving from artistic expression to political expression – that’s perhaps the clearest word. In politics we never make feelings, we make politics. When it comes to films, you have to stay in the right frame of mind, the feeling is created without the need to explain it in logical terms.

Can you clarify the meaning of your mise en scene, when it conforms to a specific geometric schema, which is virtually identical at certain points in most of your films?

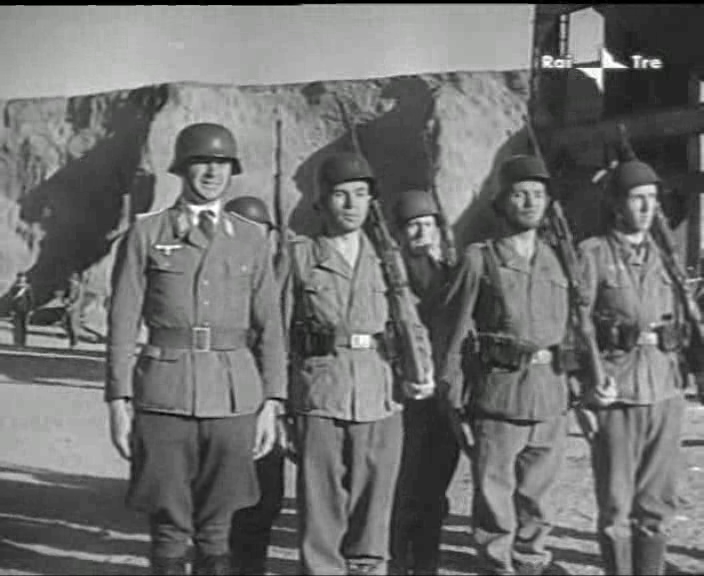

You say it very well – geometry. There are scenes where this geometry is so overt that, perhaps, it bothers the spectator. So, in The Flame that Never Dies, the whole ceremony during which the man is going to be shot was built according to an almost maniacal geometric form, composed of volumes and underlined by dollies, a geometry of longitudinal and transversal lines that can appear formal. Similarly, in Legions of the Nile, the battle at certain points tends to become a bit of a ballet. I can hardly explain what I want to express, because it’s born of a deep-seated need in my mind. There are situations in which I feel the need to orient the totality of events according to a certain construction in the image…

Isn’t it first and foremost the desire to totally master the world at a certain moment?

Yes, to make it sound a certain way. To be clear, I love Bach too much not to try and make Bach into a film. The performance scene in The Flame that Never Dies is a bit Bach-like, i.e. built with vertical and horizontal sounds. The form of this scene was born of the need to give material things an order to free certain things from the mind.

It’s very much a liturgy.

A man is going to be killed with great ceremony. What should we do? A liturgy. The orders given by the platoon leader sound like a mass, because the miracle is happening. The body will fall to the ground, the soul will be free. Something is going to happen. It’s another way of looking at death. I could say the same, for example, about crowds. Crowds always give me nightmares, like something inhuman. So I try to give them two diagonal directions, because such a composition makes them a little more human to me. Order in disorder. I believe that man is in search of order. That’s why, through science, he’s succeeded in freezing the disorder of creation in an order.

This geometrically shaped liturgy is also the very movement of tragedy. In other words, it establishes an inescapable order, an unstoppable mechanism.

Yes. Once you’re in, you can’t get out. If you start with this principle of geometry, you have to go all the way, free yourself. The miracle has to happen, whether it’s the miracle of feeling, the miracle of death, or the miracle of life. Once I’ve done that, I can abandon the liturgy and return to a nonchalant disorder in the characters’ situations. I’ve reached the end of a certain game of language.

Isn’t there a danger in this ordering of events, that of theatricality?

You can’t make a comparison between cinema and theater, because in cinema, geometry is rhythmic: in short, it’s a geometry of camera movements and a geometry of actors’ movements in the camera. It’s a geometry of montage. Sound itself, the interplay of sound, bring it closer and further apart. Everything becomes geometry. Whereas in theater, geometry is purely formal, a composition within the confines of a tableau. It’s not a creative geometry. However, yes, there is a danger. In Die Nibelungen, Fritz Lang’s geometry is a little decorative and superficial. Yet when I saw this film, I was quite young and I’ve never forgotten it. Even in its exteriority, it gave me something that has stayed with me: the stairs, the lady in white, the lady in black, with their suite in black on one side, in white on the other. All this was built up in a rather theatrical way, and had a rather expressive, charged presence on screen. When Fritz Lang made this film, he wasn’t yet the great Fritz Lang he is today. But we could already see his search for a formal solution to problems of feelings. Dressing Brunhild in black and Kriemhild in white was a little childish, it belongs to the expressionist theater, but nevertheless giving a direction. The same goes for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. These experiments interested me at a certain point, and I was looking for what could be drawn from them.

You have, in a way, prolonged them by internalizing them…

Yes, you said the word: “internalizing.” A moment ago, I was talking about the power of the camera. I’d rather say: the intelligence of the camera. You think you’re its master, but then you discover that it’s been working on its own behalf. It has seen for itself, the lens has a power of its own – I thought I’d captured an actor’s expression, I see the rushes: we’ve got another one. So what happened? It was the camera that changed it, that chose. That’s why you have to know it well. You have to have a good relationship with it, a friendship, because if you don’t, it plays nasty tricks on you.

No other artistic medium possesses this ability to “get inside” with a camera. The painter gives us interiority through the power of his brushstrokes. An abstract painting can express extreme interiority. I even think that in painting, interiority is achieved much more through the non-figurative than through the figurative. Whereas in the cinema, we work on the concrete. An abstract image on the screen is disturbing, it constitutes something incomprehensible. On the contrary, the concrete nature of the camera enables a spiritual journey that goes beyond the form of the face to enter the feeling. But, to do this, we must first and foremost renounce that which, by designating the character, separates us from him or her. Words and dialogues are the enemies that we need to destroy in order to enter the interiority of consciousness, spirit and suffering. When we go beyond a certain level of sentiment, when that sentiment has to invade the spectator’s interiority, it has to invade it at the same time as the character’s interiority. Words create a distance, a subject-object situation. While the silences already establish an identification. And the silence will continue, will continue until the moment when it is no longer silence, that is, when the spectator is no longer in a position to say to himself: “The character no longer speaks.” At that point, he or she can begin to identify with it. It’s not easy to determine the length of silence needed to reach that point because, unfortunately, few spectators have the same receptivity. It is therefore not good to prolong it so much that the most receptive get tired of waiting, nor to shorten it so much that it does not reach the consciousness of the majority of spectators. I did this with Traviata ’53, where the best sequences are completely silent.

Have you arrived at this paradox that, since the invention of talking pictures, the best films are silent?

It’s true! But believe me, whereas silent films forced us to look for equivalents to speech and sound, today we’re no longer slaves to words. Since films are talking, and so many words have been said, we’re free to remain silent. With the invention of sound, we’ve got sound in the bag. In The Flame that Never Dies, when people run to the place where the man is shot, and in the whole execution scene with the preparations, it’s not words we hear, it’s sounds. The orders given to the soldiers, the translations of the interpreter, sounds that we are not obliged to understand, to follow like a text, because they are, in a way, the sounds of nature. The announcement of death to the woman, in the first part, is also a completely silent piece. In this last scene, moreover, the importance of silence is even clearer. The man bringing a letter from her husband asks: “Good news, Madame?” She starts to read and replies, “Yes, yes, good news!,” then runs back to the house, rereading the letter and shouting, “Papa, Giuseppe has written!” And she enters and sees the face where the misfortune is inscribed. From that moment on, no more is said until the end of the first part, when the little child begins to cry.

Likewise, in Traviata ’53, there are four entirely silent sequences. The one in the railroad sleeping car, quite long and full of feeling, where we witness the despair of the woman who has sacrificed herself. But she can’t see her sacrifice through to the end, because something inside of her has cracked. Even the man understands this, and that there’s nothing more he can do. There’s nothing left but the expectation of an end of some kind. There’s the tuberculosis scene, there’s one of the last scenes where he discovers that she’s dead, and there’s the scene where the young man, in the bar, hears the girl is in Milan, whereas she had said she was leaving for her family. He understands that the industrialist, who was traveling during their lovemaking, has returned to Milan. So he jumps into his little car and pulls up in front of the villa, where the industrialist’s car is already parked. The sexual relations between the old man and the young girl take place in the eyes, on the face of the young man who, outside, waits to see who will leave the house and get into the car… In front of the car, seen from a distance, the driver walks up and down, there’s this atmosphere of waiting, then the door opens and he sees the man get out. It’s a long sequence in which the silent feeling becomes very clear. At this point, it’s no longer necessary to convey the situation through dialogue. You just have to leave the space to the invasion of the secret feelings you need to express. This is what I call internalization. In this sense, I hope to make a film where the problems of interiorization can be easily transmitted to the audience, it’s an adaptation of a novel by Bernanos, The Crime. There’s a very solid detective story in it. But in this policier framework, there is the relationship between man and crime, man and justice, man and other men, and man and God. I believe it’s possible to make a drama that reaches the audience very well and, at the same time, gives the audience the opportunity to penetrate the interiority of a conscience, to participate in a drama, but… dramatically, with full participation, a result we seek every time we make a film.

What role does the set play in your work?

The cinema set is tricky to build, because it must be valid from all angles. With the camera, with the characters, we move, we search. I would say that the ideal set would be one that would change with the movement of the actor’s feelings. For example, with changes in colors, I can achieve a consonance of settings and feelings. But since it is not always possible, it is necessary to manage to give the set the right proportions, movement and colors, in a way that they match the fundamental sound of the scene.

This question of the set brings us to that of cinemascope.

I thought that cinemascope, at first glance, was a little industrial madness. I didn’t really understand its possibilities. I found that it suppressed certain camera movements, broke a certain rhythm, weakened the montage. It was perhaps, quite simply, as always in the face of technical improvement in the arts, timidity with regards to this new machine that had been invented. In short time, I saw that the public had adapted to the immensity of the image. Their eyes were already fixed on the focal point that interested us…

What has not been resolved yet is the composition of the image. The ideal would be to have a change in the forms of images. To sometimes use the standard format, sometimes a vertical cinemascope, sometimes the horizontal cinemascope. But, with all the respect I have for Abel Gance, it would rather be a fairground attraction than an artistic expression. So, we can solve the problem by dividing the image. That is to say, more generally, by working on the image. For example, if there are too many things to right and left, we reduce their importance, we restrict the image to its center of interest. We always said: “In cinemascope, you have to stay far from the actors.” It’s an absurd idea. You have to be close to the actors. They can be placed sixty centimeters from the camera if the lenses allow it. We can highlight a detail very well, provided that the rest of the image has no importance. We have to do what we were talking about earlier, the internal editing of the image itself.

The advantage of cinemascope, I found it in the film that I am currently shooting [Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis] and which is in Super Technirama, that is, cinemascope even a little more perfected, a little more enlarged, with a camera still a little more “mammoth” than the others, therefore a little more difficult to move. But apart from this excess of gravity, the advantage of such a format is that it corresponds to an atmosphere. The horizontal movement which is the dynamic of this type of adventure (a very strong man, very wide things) corresponds to the width of the screen. The movement along geometric lines is reinforced, because the diagonals of the cinemascope are extended and less vertical than in the standard format. We can therefore play much more strongly on their intersection. In my opinion, today cinemascope is a means of “writing cinema.” There are films that must be made in cinemascope.

Among the films I would like to make today, I would make in Technirama Life is a Dream (Pedro Calderón de la Barca), and in black and white cinemascope another film based on a novel by Dino Buzzatti, entitled Desert of the Tartars… It’s a strange novel that takes place in a military fortress, in the mountains. And I would do this film in black and white Scope, because I feel that the subject and the setting require the magnitude of the image, and I am also sure that in the midst of this magnitude, we can enter into a consciousness and extract the secret of feelings. But when it comes to a film of today, the film of our daily feelings, the proportions of cinemascope do not correspond to the proportions of our life. Our quotidian life is not done in cinemascope, but in a standard format.

Cinemascope is not at all made to human standards in the sense that Le Corbusier, for example, builds his houses according to certain human proportions, his Modulor.

This is precisely why I say: it is a poetic format. A format for telling certain fables, certain stories which are close to man, but not quite in man. If we want to make a film “inside of man,” I’ll say, frankly, that we must take the Pythagorean proportions of the standard format.

There is one constant in most of your films, the presence of physical suffering. The human being is nailed to the world and struggles with pain.

I’d say that, in a general way, I consider from a dramatic point of view, two things in human life. One is failure. We are made up of a part which is the spirit, the soul, and which has the desire to express itself, in love, in hatred; it is the most beautiful and the worst feeling, it is the mind in all its possibilities, which desires to communicate with others, to participate, to identify itself. But the vehicle of this spirit is the body, with its faults, its limits, with its suffering. And the limits of the body trap the soul in the eyes, in the face, in the skin, in the tensing nerves. It is therefore a form of expression that suits cinema as an art.

A physical tragedy.

Correct. The continual failure of the mind, which cannot free itself, which participates in the suffering of the body and inflicts it on itself. So much of the suffering of our bodies arise from the soul, much more than the opposite.

Suffering interests me more than joy. I see joy as a force to penetrate pain; enjoyment, like these sounds in vertical flight which rest on a horizontal axis, suffering precisely. I beg your pardon for quoting Bach so much, but I believe that in music, Bach gave us something that we have not yet managed to give with cinema. This is why I take him as an example.

The second aspect of human drama is the impossibility of identifying with something. What is love? I speak a bit as an existentialist, but these are terms which correspond to our feeling about life today. Love is the desire to identify with the loved one. This possibility of identification is destined, as always, to failure, because our bodies obstruct it. Kissing a woman, what does it mean? A physical attempt to identify, to take part, to enter. The perfect point of love is the moment when man and woman seek to give themselves over to each other, to erase themselves in the other. This attempt is a failure, and a dramatic failure. This is why, in love stories, what interests me is the force of this love and the impossibility of reaching this point of perfection; it must erupt into drama.

In all your films there is a certain cruelty, a certain tendency to torture women: how should we interpret it in relation to what you said about physical suffering and love?

The human being is like a vase within which the soul is like a liquid. The vase is constructed in a different way depending on whether it is a woman or a man. And I find that the female vase, or vessel, contains many more possibilities of despair and suffering, more to give, than man. Man is focused on the spirit rather than feeling, on moral suffering rather than physical suffering. Perhaps, in matters of the spirit, he places himself higher than the woman, but in feelings much lower. In cinema, I especially look for feeling. That is the reason why I am much more interested in women than in men. It goes without saying that in man, there is also a feminine side, even in the most brutal man. It’s not a question of sex, but of the balance of the character. Naturally, it’s the side of man that interests me the most.

As for eroticism, it is an external aspect of feeling, a moment of feeling which ends quite quickly. An accident of sentiment. I am interested in it within the limits of the accident, but not beyond that. Therefore I don’t think I will ever make an “erotic” film. A film of feelings where there is an erotic moment, yes. But as the exact moment of the feeling, and not in itself.

In your films, the physical and moral presence of children is often defined in a fairly precise way, which is not the case for many filmmakers.

In children, what I find extraordinary is the partial presence of the man. Man is in the process of being built. The problem of this construction which progresses every day, which begins to participate in certain things and refuses others, is very important. Unfortunately, in the cinema, you have to be children with children. We cannot do what children do in literature with words; or like in music with sounds (you remember Peter and the Wolf by Prokofiev). And that is almost an insoluble problem, because the child who plays, plays out of tune. We can take snapshots of the children, we can’t make a whole film with them. There is a great master of children in Italy, it is De Sica. De Sica is the one who gave us the truest children, the most representative of man at his birth. I have seen Bicycle Thieves several times for the child. It is a perfect example of a child who reached a certain truth of life, by discovering suffering and humiliation.

We would like to talk about the children characters in your films.

I think they are still very false. False because they are fictional. We can make kings, queens, barbarian soldiers with enough truth. What is taken as false can be made true within the limits of the story itself, through a certain research into the construction of the character and the play of the actors, from which the child escapes. The child, even in costume, remains a child. He does not adhere to this type of story. I believe in children in everyday life, in today’s children. With them, we can arrive, to a certain extent, at a truth. It takes a lot of patience and experience.

Between the child and the man lies puberty. The problem is mentioned in The Flame that Never Dies, but it is a question of a joyful, unconscious puberty. I wanted it to be unconscious because it is the story of a man who makes what we call a “qualitative leap.” This means that in man, at a certain moment, continuation is not respected. There is a break and a leap forward. So, I wanted everything preceding the leap forward (located in the last 600 meters, the final section of the film) to be simple, joyful, almost banal. The young man’s adolescence must have been fairly candid. The woman’s love and approach must have led to a little laugher, a bit of a laugh, like the little dog that walks poorly with his big paws. Unskilled finally, with women, as he is unskilled during the war, and in everything he does in the seminar. I wanted it to be clumsy because it must arrive at this “leap” which, in the religious man, constitutes the gift of heaven, holiness, with great humility.

What do you think of neorealism as defined by Zavattini?

The term neorealism is not very appropriate; we should rather call this school neo-Verismo1. “Tot capita, tot sensus,” as the Latins used to say. And everyone can say what’s on their mind, with their share of right and wrong. I think the importance of neorealism lies not in the meticulous description of everyday life, as Zavattini asserts, but rather in the effort to liberate certain conventions from cinematic means. One day a naval officer called De Robertis – he died two years ago – was given the opportunity to make a film about a sinking submarine. He made a completely documentary film, with real sailors as actors. It was a dramatic film, with feelings and situations, but made in the spirit of documentary. Another thing: this gentleman didn’t know the technical possibilities of the camera. He had no idea how to link one shot to the next. But he shot anyway. The result? A very interesting one. The inadequacy of language became an element of truth. It was from this film that neorealism was born in Italy. We realized it afterwards, with Rome Open City, the first monument to it. Rossellini filmed it in singular circumstances and a singular state of mind. All the studios were destroyed, no one was working, so he filmed real things out of necessity. They shot in cellars, with terrible lighting. The cinematographer, who was a very good technician, said to me: “You can’t make films like that, you can’t light them.” But the result is remarkable. These paradoxes allowed us to discover that an adherence to everyday reality can be born of a certain technical awkwardness, of a material impossibility of achieving formal perfection, in particular with the lighting that the Americans had proposed to us as a criterion of extreme mastery of cinematographic language. We discovered the beauty of unfinished things. Michelangelo left sketches that possess extraordinary expressive power. This corresponds more or less to the discovery of neorealism. Afterwards, having obtained certain dazzling results by force of circumstance, we formulated the theory, voluntarily and without necessity placed ourselves back in the same circumstances, and refined. Rossellini is the grand master of the genre. He did everything he could think of with ease and absolute disregard for the rules. Because he showed us the possibilities and also the limits of neorealism, it’s hard to talk about it today. But this long-gone experience certainly is something important. I could draw a parallel with another experience, this one poetic, and in fact the opposite of realism. During fascism, with the arts somewhat politically controlled, poetry became hermetic, where language was completely disguised in sound, in successive illuminations, thanks to words with ever ambiguous meanings. This experiment, which was very strong in Italy for several years, had the same character of historical contingency as neorealism. These are the extreme movements of a moral, spiritual, poetic necessity; at the end of these experiments, we see the emptiness, the limits, we go back, we start again from another side, but it’s not lost. Today, to say: “This film is neorealist” would seem a little strange. But to say that a film is born from a neorealist experience means something. I think our cinema today contains the consequences of these experiences. Antonioni has his own particular style, his own themes, but everything that is no longer neorealism benefits from its results. What is La Dolce Vita if not neorealism transformed and integrated into a poetic experience of today?

This is a historian’s point of view. Would you like now to define your personal situation with regard to the neorealist experiment?

For me, the problem never arose in those terms. I shot The Flame that Never Dies exactly at the time of neorealism. But I can’t see any common ground between my film and that school. The elements were completely different. The Germans in Flame were not the Germans of neorealism, but Germans of all centuries. My hero was not the particular hero of this particular episode. He was the man who makes the “qualitative leap.” And similarly, all my other films, including Traviata ’53, which at first glance appears to be a neorealist film. In neorealism, there wasn’t this desperate search for a certain deformation of the soul, this sense of human incomprehension. It’s a romantic idea that has nothing to do with realism. It doesn’t matter that the story takes place today, or that it’s set in the streets of Milan. It could, I think, just as easily have taken place in central Africa. The settings weren’t important from the point of view of realism, but in terms of despair, incomprehension, the impossibility of adhering to each other, this horrible thing: by loving each other, we can manage to ruin each other.

So I’ve always been interested in neorealism and its results, but never had the opportunity to participate. Perhaps, when it’s all over, I’ll have a chance to make a film in that spirit…

However, it seems that if you hadn’t made a neorealist film, it’s not so much because you hadn’t had the opportunity to do so, as because the very idea of mise en scene as you conceive it, is quite contrary to this approach. By your desire to go beyond appearances, by your interest in the crisis, its formation and its explosion, you are necessarily on the side of Racine.

To sum up exactly what you’ve just said, I’d use the words: “inner tear.” I want to reduce the limits of this state to the essential, that is, the universal. And paradoxically, I believe that the universal is contained in the singular much more than the plural, that in everyday, collective banality. A character stands out from the others, and becomes possible for everyone to identify with him: his singularity becomes universality. I say: a character, not a hero.

I always see heroism as sanctity. If there’s no sanctity in heroism, it’s only madness and egocentricity. Most heroes are abominable characters. They come from the wildest part of man. In neo-mythologism, the hero is the strong man who kills and understands nothing of souls, who poses no problems for himself, except perhaps the last Hercules, who is a little more understanding of certain moral problems. He remains a hero, but very slightly disguised as a character.

As for the character as I see it, I could give you an example with Kafka’s story, The Village Schoolmaster2. The mole is a character. And we identify with him so much that when I read this story, I felt like a mole. He’s afraid, he makes his hole, then, fearing discovery, he hides the entrance and digs deeper. Then he hears a noise, digs more holes to uncover the enemy, drills an emergency exit, then says to himself: “But what if he came in through this exit?” This character is ourselves. We are moles. The enemy is everywhere. We’re always building our little psychic, moral defense. It’s a theme I’d like to define in a film, by expressing the panic that man feels today. The fear that drives man to war. It’s communicated from person to person, and becomes collective. Until we feel strong enough to crush the enemy, we remain on the defensive, digging holes. When we feel sufficiently protected, the folly of eliminating the enemy arises. The collective madness that brought us the last war broke out in Germany, perhaps the most Kafkaesque of nations. The fight against the Jews represents exactly what Kafka said, who as a Jew had an exasperated sensitivity to such things. And I find this madness extraordinarily powerful. I haven’t yet considered making a film about it. Maybe it’s too difficult, maybe it’s an effort my muscles can’t sustain. I might be able to do it by individualizing the situation in characters instead of hearing it as a collective situation.

What is the subject of a film for you?

I think it’s a state of mind. A generic state of mind about a problem, a theme, a feeling, which slowly takes shape in the character. The abstract starting point takes shape in a character, and around that character, events come to life. I think the birth of the subject is much the same as in a novel. Except that in a novel, the idea immediately materializes in a language made up of words and in a determined construction, whereas in the genesis of a film, the idea must remain in the vagueness of the découpage, in the preordination of the material. On the other hand, while it’s obvious that the subject imagined by the director is closer to his personality than that which comes from the outside, there are nonetheless such strong spiritual communications that each of us is likely to find in other authors something more similar to ourselves than we can imagine. Among French authors, for example, I’m very fond of Julien Green. In his Journal, he wrote things that touch me deeply. Adrienne Mesurat is a story that, if I were to adapt it for the screen, I don’t think I’d change a thing, because I’m so involved in this terrible drama, this crime, this suffering, this compression, this search for an impossible liberation. It corresponds exactly to the dramatic form of my conception of life. Then there’s Bernanos. One of my greatest desires would be to adapt Under the Sun of Satan. In the meantime, I’m thinking of shooting The Crime soon, which is more cinematic, more acceptable to the public, although it does include some elements from the other book.

So we can take an already-completed work of another expressive line, another language, like the novel, adhere to it and turn it into a film. In every literary image, there is the possibility of a filmic image. Needless to say, writers always claim to have been disrespected. Writers who don’t understand the language of cinema. But those who do, realize that it is the equivalent of literary language, even if it deviates from it in letter, the essential thing being that it remains faithful to the spirit. In fact, the task of transposition is so difficult that it is almost always immediately abandoned, and the literary material is transported into the film. It’s immediately obvious that this is a failure, because it remains filmed literature. But if you have the strength, the perseverance and the will to succeed, I think that most of the literary works that correspond to our true feeling as film authors can find an exact equivalent in the image.

Is this equivalence the real aim of your effort, or does the literary work play the role of a springboard for your inspiration, of a material, in the same way as a simple screenplay?

I think you’ve expressed the truth, albeit a little sharply. Directing is not an abstract thing, it’s perhaps the most concrete thing in the arts. I work with actors, with sets, with the camera, and I work with the story. That’s one of the concrete elements. It’s clear that I have to transfigure it, transforming what is literature into mise en scene. But I can’t say it doesn’t exist. Through this re-creation of literary elements, we arrive at another form that may betray the original work in part, but remains internally faithful to it insofar as the filmmaker finds himself in it and recognizes himself in it. It goes without saying that if I adapt a work that doesn’t interest me, that doesn’t correspond to me, detached from me, living for its own sake, I’ll make the film, no doubt, a film that may be perfect, promised to be a great success, but in which there won’t be the thrill of creation, that something that touches when artistic expression has reached its goal. A film can be a complete failure, but there’s small passages when you see the poet.

How do you approach the problem of directing actors?

I believe the actor is a being who, the more he is an actor, the more sensitive and delicate he is, the more he needs to be spared. I’m talking about real actors, because those who aren’t, you have to fight with them, force them, draw them in piece by piece. But the real actor, the one who is mature, who has the desire to express himself, the gift of communing with the audience, the first thing to do is approach him with love, with interest, to understand him, even his faults. Don’t jerk him, don’t tap him on the shoulder. Take him by the hand, help him, flatter him, give him self-confidence, give him the joy of expressing himself and say: “Yes, yes,” even if sometimes it would be better to say “no.” You have to say “no” in certain circumstances, but not in others. You have to explain yourself at length, ready to give up what you set out to achieve if you don’t succeed. Finally, working with an actor is a marriage. Marriage is a continual effort of sparing, giving and sacrificing for one’s life companion. With an actor, it’s a bit like that. And, above all, you have to be careful not to impose a “sound” on him that is not harmonious. The director’s secret is to use the actor as well as possible for his role. Then, to help him adhere to it; to support him, to strengthen him without showing the effort. This is for real actors.

Then there are those who only have one job. You can get a lot out of them, but it’s a different job. It’s a job in terms of their craft. They have such a solid craft that you can explain to them very clearly what you want, and they try to give it. We adjust a little harder, a little less, a little more to the right, a little more to the left, until the expression adheres to the character. Working with these actors is like driving a car: you change gear, you turn the wheel. In a certain sense, for a director, these professional actors are more satisfying than the “poetic” actors…

Do you go so far as to allow this type of actor a certain freedom of action?

No, not freedom of action, but collaboration. I work with the actor, looking for a mutual trust. The Confiteor. We have to confess to each other. The director of the time, if I may say so, the romantic of staging, the dictator who gave orders and wanted them to be carried out, is making a very big mistake. No, the director gives advice and wants it to be carried out. He himself asks the actors for advice and suggestions. When an actor says to me: “I can’t do that, I don’t feel like it, I’d rather do it this way,” I always listen, because it would be a mistake not to listen to a man who has his own sensibility and whose possibilities are ripe, especially if he had understood the character well. I could reply: “No, I don’t agree, please don’t do it like that.” But why give up this fruitful collaboration to an outside authority? I believe that in our work, lack of humility is the greatest danger.

Of course, I’m speaking theoretically, because in the film I’m currently shooting [Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis], there are very few actors. There are guys who play their roles as well as they can, with their important physique, their beautiful gestures, their Roman heads, their costumes that make them look like pies rather than men. With them, the work is of a completely different kind. It becomes much more mechanical, and above all much simpler, because only the fundamental tone is given: you can’t perform a Beethoven symphony, you simply perform – not even a sonata, but a sound. I no longer work with an orchestra, but with a tuning fork. To one I give the F, and “tang!” To the other I give the E, and “ting!” he works in E. I was talking about the search for the inner tear. Right now, I’m working on films that require construction, an outward grandiloquence, the hero in the true, ancient sense of the word, the myth at last. So I have to look for a naturalness – not the naturalness of everyday life, but the naturalness of costume. Every film has its truth. A film in costume has its truth in costume. The costume must be worn in a certain way, the movement of the mouth, the expression of the eyes must be appropriate to the costume and the set. It’s a particular naturalness within the unnaturalness of the set and the situation.

Then there’s the last kind of directing, when you’re working with non-professionals. Here, I refer to De Sica, who is truly a specialist in the field. He does what I sometimes I try to do, with the dwarf Salvatore, for example, who is not an actor. What do you do? We try, make him say a line; no, it’s not right – “So, let’s see, do it like this.” It’s still not right. Then, at a certain point, you catch a successful snippet in the little scene you’re rehearsing. That’s conquered; but be careful not to lose it, because if they’re not a professional, they lose things immediately. You have to hold on the point you’ve made, and modify the rest according to this fragment of the non-actor’s truth. It’s a very slow and often thankless job, but one which, thanks to this lack of “professionalism,” of craftiness, in certain films of the neorealist movement, has produced some very interesting results.

This interview was originally published in Présence du cinéma n° 9, in December 1961. The interview was conducted by Michel Mourlet and Paul Agde. The translation was done using this French text. Translation by Jhon Hernandez. Thanks to Diego for his assistance on the translation.

FOOTNOTES

- Verismo was a literary movement in Italy from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement’s goal was to present life objectively, often of the lower classes. ↩︎

- Cottafavi appears to be conflating The Village Schoolmaster (which is about a matter concerning the mole) and The Burrow (which is about an unnamed animal, quite possibly a mole) and its anxieties. ↩︎

1 comment