It has been 3 weeks since we published our nominally bi-weekly grid, our offices closed for the Thanksgiving weekend. In that time we published Jhon Hernandez on La Grande Maison Paris, the disappointing 2024 continuation of the beloved Japanese drama series La Grande Maison Tokyo. This continues a series of writing about Japanese Drama series that began with a look at the seminal Kimi wa Pet back in November of 2023. Here the question is about the borders within which filmmaking – whether in movies or television – takes place, and which do or do not allow for the alchemical processes we broadly (sometimes polemically) refer to as cinema.

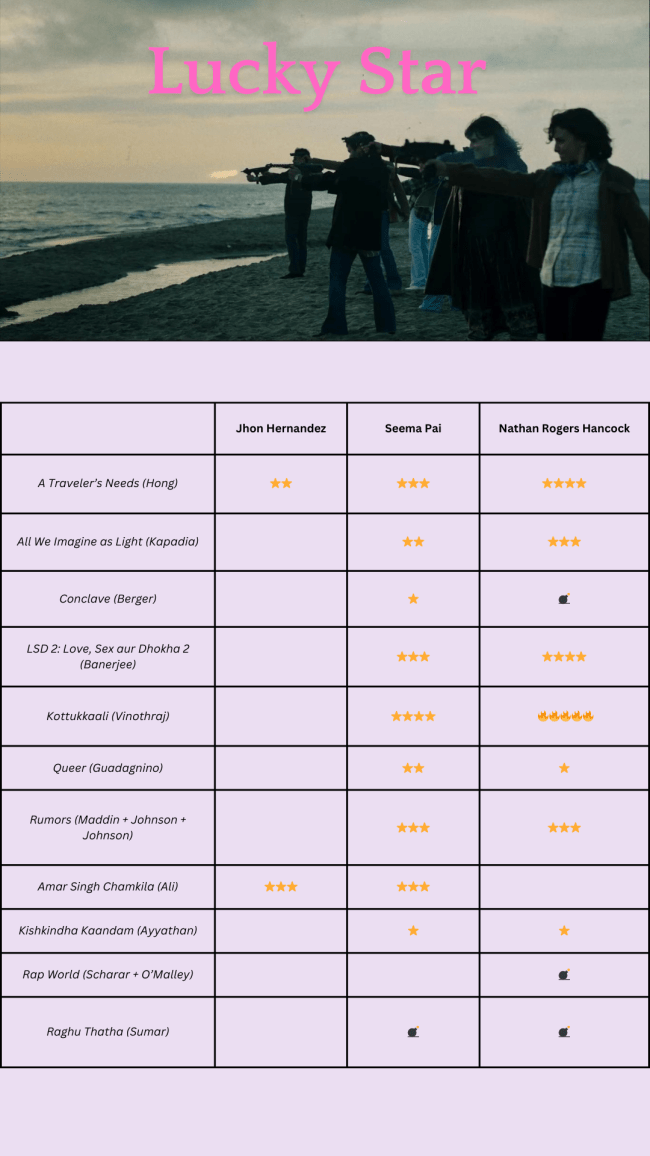

It is a question that has been on our minds recently. The final months of the year, as reflected in the grid above, are often a time to catch up on recent releases, to see major festival films getting end of year theatrical engagements or slipping quietly into the mess of the streaming ecosystem, or to spend time with the year’s final major releases (Sukumar’s Pushpa 2: The Rise opened globally just a few days earlier). It is also a time when, due to any number of external factors – familial or social obligation, the tyranny of children, the ignominy of airline travel – we end up spending time with movies we otherwise would not. That these experiences sometimes turn out to be negative does not mean that we do not live, eternally, with hope.

Conclave (Edward Berger)

Remove the perfunctory talk of faith, the ceremonial window dressing, the plight of nuns, and you can find what amounts to the emotional core of Edward Berger’s film – an efficient and likable middle manager, comfortable in his job as he inches towards the age of retirement, terrified by the prospect of being promoted into a leadership position. It is tempting, to paraphrase Denis Ménochet’s despairing President of France in Guy Maddin, Even Johnson and Galen John’s curious Rumours, to view the film allegorically – for the 2024 American election, the 2020 American election, the All Quiet on the Western Front Oscar campaign?

In the end it doesn’t matter – the film’s own internal logic demands that the vote should fall to the great Sergio Castellito’s charismatic reactionary rather than to Carlos Diehz’s saintly cipher, as it does following the latter’s speech imploring the community to look to their better natures in the face of terrorist violence, wishful thinking so at odds with the previous two hours of petty venality. Raiph Fiennes middle manager, we suspect, would retire happily either way.

The presence of Castellito, the star of Marco Bellocchio’s My Mother’s Smile, the 20th century’s greatest film about the Catholic Church (Bellocchio’s Kidnapped, from last year, is the second), almost demands a comparison, but that is a red herring too – despite the iconography and procedural detail involved Conclave has more in common with the fantasy vampire election of Lucius Shepard’s The Golden than, say, Nani Moretti’s We Have a Pope. The isolation is the point, the sealed edifice, another reminder that years after the lifting of the Covid lockdowns Hollywood is still more comfortable with isolation than with the world.

The week before I watched Conclave I spent an international flight reading two classics of British science fiction, Non-Stop by Brian Aldiss Inverted World by Christopher Priest, two books set in closed, impossible edifices, where the apprehension and understanding of the nature of the closed world you live in is both necessary and painful, even apocalyptic. Here there is no outside, no apprehension of the shape of the edifice of the Church, nothing but an empty (if lavishly appointed) venue where the cast can spin plates for our amusement.

Queer (Luca Guadignino)

A bit of hypocrisy – I will say with a straight face that, whatever its limitations, the creation of Allu Arjun’s Pushparaju is enough to justify the existence of Sukumar’s Pushpa: The Rise and, presumably, its 3 hour and 20 minute long sequel, but deny the same grace to Queer, even while acknowledging the extraordinary achievement that is Daniel Craig’s Bill Lee? Burroughs was, by the end of his long life, one of the most photographed and recorded of counterculture figures, a sepulchral figure in a dandy’s anachronistic uniform, an impenetrable public performance from a writer whose most famous work often seemed to take the shape of a series of virtuistic, extravagantly camp character monologues. The early Burroughs, of Junky, Queer, and The Yage Letters is a different proposition, a contradictory mix of performative pulp and dissociative autobiography, all of which somehow seems far more contemporary than the canonized later work, impacted as it is by further decades of pastiche, now many times removed. Peter Wellers, in Cronenberg’s version of Naked Lunch, had the advantage of playing a man already devolved into fiction. Craig plays a version of Burroughs only partway there – an aimless junky adrift in a foreign city, who reads Under the Volcano as if it were an instruction manual, who owns multiple typewriters but never seems to write, immaculate dress not yet turned into costuming, a devastatingly handsome man who seems to nonetheless emit a kind of unsettling aura that repels those around him, bursts of verbal invention and “doing voices” that slide all too quickly into alienating or abrasive, an inability to read a room.

I confess to having not seen a Luca Guadignino movie since 2009’s I Am Love, and an entire career has happened between then and now, but I was shocked by the facility with which he handles the dramatic material – a courtship that moves from bashful courtship to hungry sexual attraction to the point where, without either party realizing it, those same gestures become distorted or grotesque; a series of friendships held at arms length – and at how poorly he supplies an interpretive framework with which to structure them. Opening with a dreadful Sinead O’Connor cover of Nirvana should be enough of a warning that Guadignino is only tenuously in command of his iconography, repeated allusions to the “William Tell” shooting incident that claimed the life of Burroughs wife provide less an interpretive key (as they did in Cronenberg’s film) than they seem to suggest an inability to trust the material at hand; a third act detour into the South American jungle in search of ayahuasca and telepathy suggests nothing more than dramatic desperation and festival film cliche.

And once we have a contemporary English language film that seems almost surreally empty, an impeccably groomed Potemkin Village populated by no more than a handful of people, a decision that can be easily defended, but which nonetheless suggests a contemporary film landscape in which impressive tailoring is far more accessible than human presence. The constant mention of a bar where the really out queers go suggests less the sense of a vibrant off-screen space than a theoretical El Lugar Sin Limites environment that the film doesn’t have the curiosity (or the budget?) to imagine. The comparison is as ridiculous as drafting Bellocchio in relation to Conclave – the gulf between the sensibilities of Guadignino and Ripstein (and Burroughs and Donoso) is at least as wide as 1978 and 2024 are in time, as the differences between the Mexican market and post-Covid, post streaming Europudding – but it is an example of a film of isolation that exists within (in opposition to) the outside world, within a contemporary literature, that seethes…