The Gift of Tears

by Jean-Claude Guiguet

Recently I took a friend passing through Paris to visit an preserved old neighborhood of the capital. It was a sunny Sunday in October. While he walked, the friend told me of the affection he had for his brother, whom an illness had taken away four months earlier, in the prime of his life. We crossed the crowds of walkers under vaults of the Place des Vosges. Sometimes their number forced us to walk along the gates of the central garden… I forgot to show my companion the majesty of these places that he did not know. The purpose of the walk was in turn forgotten. I couldn’t even meet his eyes anymore. He was crying.

He cried like a child without caring about passers-by. His face radiated a singular, extraordinary beauty, far removed from any conventional model. In the light of this beauty, one could see the trace of an unhealable wound so deep that I suddenly felt a feeling of boundless love. I should have held him in my arms so that he knew that someone beside him could understand this pain, and share it.

By timidity – or by cowardice? – I didn’t hold him against me. I’ve known ever since that moment that I will never forget this beloved face on which I sensed a distress that nothing, especially not time, could make disappear.

Among the truths of nature, we always forget the curse that makes us unstable before the banquet of life. That Sunday, I saw the awareness of this curse through the tears of a young man who had no idea to what inner region, what melancholy, intimate and secret space, his emotion had brutally thrown me. This look expressed a certainty: sometimes the force of destiny overtakes us and takes away our existence, leaving us with no other choice than the one towards which we are irremediably drawn.

In the cinema, when a film invites us to witness this certainty embodied in the burden of characters swept up in the inexorable movement of life, we share with them a part of their affliction or misery. At its best, this sharing of individual tragedy is akin to compassion; at its worst, it’s the exhibition of misfortune displayed like a commodity. On one side, the nobility of Douglas Sirk. On the other, the complacency of Jaco Van Dormael. A Time to Love and a Time to Die (Sirk, 1958) and The Eighth Day (Van Dormael, 1996), there’s a world of difference between melodrama and mélo.

We’ve all noticed at some point the not-so-subtle nuance that separates mélo from melodrama. So as to not get bogged down in a tedious inventory of little interest, let us note in passing that the pejorative coloration of the first term does not necessarily apply to works in the melodramatic genre alone. It indiscriminately embraces any cinematic narrative that gives free rein to the often crude strings of these voluntarist dramaturgies of self-indulgence and artifice. When a film is described in this way (“it’s a mélo“), the definition takes the place of a sentence. Condemnation is implicit in the choice of term. So we’ll leave it at that, a part of the secondary history of cinema blurred by creating a confusion that’s as pointless as it is sterile. And since I have begun this text by rekindling a personal emotion, I shall endeavor to assume until the end of these ramblings my own subjectivity in relation to this melodramatic notion, which has always represented for me one of the surest means of access to the express heights of beauty. Let’s understand the term in its most sublime sense, and for once give Baudelaire his due. When he makes Beauty speak, she murmurs, “For I have, to enchant those submissive lovers, Pure mirrors that make all things more beautiful: My eyes, my large, wide eyes of eternal brightness!” So, first of all, the gaze: its truth, its force, its light. That of Clara Calamaï under the bridge in White Nights (Visconti, 1957), her intense, excessive gaze, magnified by the depths of a distress without remedy; that of Shirley MacLaine, imploring, ingenuous and defenseless before her rival in the high school classroom in Some Came Running (Minnelli, 1958); Barbara Stanwyck, shaken by the violence of a crying fit, as she fills her coffee bowl in the kitchen in Clash by Night (Lang, 1952); Jacques Perrin, the wounded teenager in Family Diary (Zurlini, 1962), with Marcello Mastroianni lying next to his brother by chance, on a makeshift bed… Vivien Leigh’s gaze meets Robert Taylor’s in the night in Waterloo Bridge (Le Roy, 1940), Sophia Loren’s lost gaze as she searches for her dead child in the swamps of Woman of the River (Soldati, 1954), or Nadia in Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti, 1960), as seen through the eyes of Annie Girardot, at the height of her dramatic genius. Nadia, the broken, shattered woman, staggering barefoot in the mud of the wasteland after the rape, Nadia destroyed and imploring: “Rocco! Rocco! Tell me something…”

The gaze concentrates emotion, or gives rise to it. It is both source and receptacle. How is emotion born? All it takes is a word, a gesture, a fleeting vision, but placed at a certain height. It is always a living condensation inscribed in a dazzling moment… Emotion circulates away from the vital centers regulating the ordinary of our elementary sensations. It is a sinuous fluid, gentle but implacable, running through the nervous system shaken by a sudden and indefinable visitation. The unspeakable nature of this shock wave brings with it tears. “Why is it that warm, rainy winds inspire a musical mood”, asks Nietzsche in The Gay Science. The answer belongs to the mystery of beings, as much as that of creation, also escaping any form of rationality, and that is very good.

The greatness of melodrama reaches us when we brush against untold things revealing, in all its nakedness, of the strange and tragic forms of life. It is the death knell that sounds in the ruined church where the doctor in The Love of a Woman (Grémillon, 1953) finds the one who could have become the man of her life, if he had not shown himself incapable of understanding the uncompromising generosity of the woman he wanted for himself alone. Here, human greatness is barred by the pettiness of an ego hypertrophied in an assertion of power that is an abuse of power, the means of inclining, breaking, subjugating the other to his desires so that he abdicates all forms of personal freedom. These are also the unforgettable an heartbreaking last minutes of Splendor in the Grass (Kazan, 1961) with the face-to-face of Nathalie Wood and Warren Beatty, these two young people passionately in love with each other who have been separated forever by prejudices and life circumstances. When they see each other a few years later, they have nothing more to say to each other, especially because there is so much untold and so many regrets to share! All that remains in this suspended moment of eternity is a mute, haggard, tragic emotion… the feeling of a definitive waste, and this irreversible observation: the only paradises are those that have been lost.

These are among others, a few examples of this unspeakable, glittering in heaven of the genre of which no one can say without shame that it is a minor genre, or a by-product of a tragedy. It is also possible to draw the dotted line of the border separating this one from that one without too much risk of error. For the characters in tragedy, the threat is within their mental and psychic structure: Francisca, the heroine of Manoel de Oliveira, Madame de…, that of Max Ophüls, or the Gabin of Le jour se lève (Marcel Carné, 1939). In melodrama, it is the coalition of external elements – social relations, the drama of poverty, the class struggle… etc. – which breaks individual destiny. Let us note in passing the danger that awaits the genre and the traps that every filmmaker must avoid: the one-upmanship in the relentlessness of this destiny too often disfigures the initial nobility of the subject, and the risk of moving from melodrama to mélo deserves to be appreciated as accurately as possible. From naked emotion to tearful pathos, it has everything that separates The Two Orphans (Riccardo Freda, 1965) and Sans famille (André Michel, 1958) from Street of Shame (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1956) and Remorques (Jean Grémillon, 1941). And when Bazin writes about Limelight (Charles Chaplin, 1952) that it is a “faux mélo“, he could add: but it is a real melodrama! In other words, a major work in which an indefinable melancholy leads Chaplin’s reflection towards the mysteries of love, on the side of the enigma represented by the heart, body and mind immersed in the great river of Time.

The emotional transport that one feels in front of these works – Limelight appears to be one of the most perfectly accomplished examples of the genre – is not due to the particular substance of the drama, which can, in this case, only satisfy the taste for mélo, this distorted melodrama, but only to its treatment. It is the ancient and famous Gidean exhortation that still says the essence of the matter today: “Let the importance lie in your look, not in the thing you look at.” We can only aim at the substance through the form by noting this obviousness: there is no melodrama in the negative sense of the term, there are only melodramatic looks, and this look inevitably brings us back to the side of the “mélo.” If the look is meant to be melodramatic, the subject becomes bastardized, the writing is absent and the substance is nothing if the film is not. The recent film Drifting Clouds (1996) by Aki Kaurismäki would be invisible without the rigorous precision of its framing and the stylistic necessity of each shot, which deeply organizes the expressive unity that illuminates the moral sense of the story, thus raising the film to the heights of art. Here, the thinness of the subject, the minor incident, the everyday as a cliché , are carried to the heights of universal human drama by an art of doing, of saying, of showing, of framing, of pruning, of giving voice to the inner song of existential distress that transcends reality to the point of pure emotional expressiveness. In short, a musical art, as any great melodrama strives to find the secret.

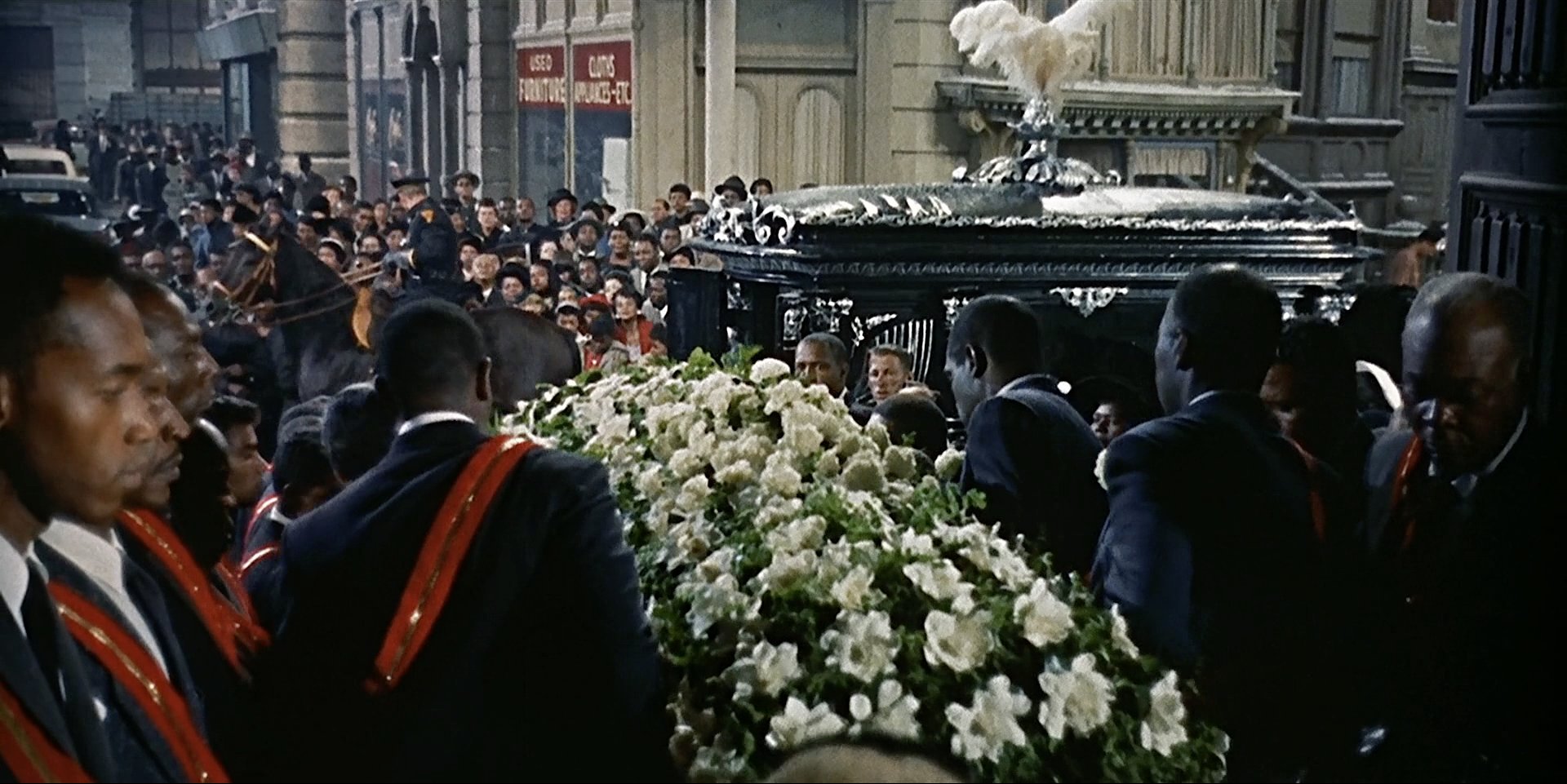

Let us not forget that the etymology of the word refers precisely to the “musical drama” (melodrama). Hence the often preponderant role of the melodic line in the internal organization of the work. The most radical audacity in this area is represented with the bliss we felt in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and A Room in Town (1982) by Jacques Demy, both conceived as true film operas. Moreover, the birth of melodrama took place at the beginning of the 19th century, when the royal and princely characters of tragedy gradually faded away in favor of the bourgeoisie, which had now reached power and business. In this context, Verdi’s La Traviata appears, in 1853, as one of the first splendors of the genre. From then on, the operatic dimension never ceased to haunt melodrama, to inflect its style by revisiting misfortune to give it aesthetic and moral depth. All the great filmmakers will know how to seize this musical opportunity with, of course, varying fortunes, but always the awareness of a decisive issue in the way of conceiving the overcoming of everyday life through the exacerbation of feelings. Music and song approach the mystery of death with greater intuition, a more radical appreciation of the secret of shadows than any other expressive medium. One only has to imagine what Contempt (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963) would be without Delerue’s extraordinary score, Senso (Luchino Visconti, 1954) amputated from Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, or Imitation of Life (Sirk, 1959) without the funeral song that comes out of Mahalia Jackson’s throat during the funeral ceremony of the black maid:

Soon it will be done

Trouble of the world

No more weeping and wailing

Soon it will be done

Trouble of the world

Or Nino Rota’s score accompanying the itinerary of the protagonists of La Strada (Federico Fellini, 1954), or A Star is Born (George Cukor, 1954), and so many others…

Having directed several melodramas myself, I would never have been able to conceive of Faubourg Saint-Martin without the help of the prelude to the 5th act of Verdi’s Don Carlos, which underlies the entire internal and dramatic structure of the film, nor could I have given substance to the metaphysical adventure of the heroine of Le Mirage without Richard Strauss and Ponchielli. Finally, how could I have recently finished Une nuit ordinaire with the special clarity that must be its own without Couperin’s Seconde leçon de ténèbres, which the project’s sponsors did not want to hear! And yet, how can we express the incessant circulation that connects the body and the mind, how better to express than through this contemplative vocalization and the voice of Hughes Cuenod, this miracle where the apparent triviality of the pleasure of the senses joins joins the soul’s aspiration towards the light of love? Rilke said that only music speaks of death. And life! When we love life, we can only think of its brevity, and therefore of its end. There are only fragile, perishable things, condemned to be sweet. Those that last do not have the power to move us and brings tears to our eyes. “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted,” say the Gospels. Of course! It is because it is precarious, that at any second it can be destroyed, that happiness exists. As life is nothing without death, which, according to Pier Paolo Pasolini, accomplishes “an instantaneous montage of our lives,” happiness has no meaning, deprived of unhappiness.

Every great melodrama is an act of poetic creation, a gesture of conquest, the desire to organize a privileged space, the affirmation of life despite the inescapable presence of nothingness. Before leaving this world, the heroine of Imitation of Life reminds the survivors of her ultimate desires: “four white horses, and a band playing. No mourning, but proud and high-stepping’, like I was going to glory.” Mouchette, Robert Bresson’s wounded child, will be content to leave the world playing like a carefree little girl, without noise, without tears, clamor… She lies down on the embankment at the edge of the pond before rolling to the water which closes in on her… an immense expanse of tears, a liquid shroud for an abandoned child. It is from the depths of this abyss of solitude that Monteverdi’s Magnificat rises, a luminous song of dizzying sweetness, the last gift of the world in memory of this little girl whom no one has been able to love.

The tears that ran through that autumn afternoon mentioned at the beginning of these lines must have found unexpected comfort in an epilogue that any competent filmmaker would have been able to invent, if the vagaries of this day, not quite like the others, had not naturally placed it on the path of our walk. A street orchestra composed of several violinists played a suite by Johann Sebastian Bach with joy. Leaning against a carriage, we remained silent for a long time in the fading light of day. These minutes, which seemed like an eternity of peace regained, consoled us for a while from the burden of existence.

This text was originally published in Le Plaisir des larmes, ACOR editions, in 1997. Thank you to Vincent Poli for posting the original French text on his blog, Les films durs à voir. Translation by Jhon Hernandez. Thanks to Diego for his assistance on the translation.

1 comment