Love at First Sight

A young boy approaches the brothers who are manning the music at a traditional Greek birthday party. He requests a song from Marika, their legendary great grandmother, but he is quickly shut down. Such songs are too sad for children one of the brothers tells him. He responds simply, “there’s no age for sadness.” The brothers comply and play the song, quickly bumming everyone out and sending them back to their tables mid-dance. This is one of the opening scenes of 2016’s, The Apple of My Eye, probably the Axelle Ropert film that makes the least sense when looking at her work.

It is the oddity of Axelle Ropert’s small body of work, an outright comedy, almost burlesque, that does away with the elegant gestures of her previous features – the nighttime romance of Tirez la langue, Mademoiselle (Miss and the Doctors), the family struggles of La famille Wolberg – and replaces them with sight gags of Bastien Bouillon fussing up a storm with his cane and pretending to be blind. It is quite blunt. Elise (Mélanie Bernier) takes her sister, played by Chloé Astor, to a doctor to discuss the sister’s recreational cocaine habit and is told that eventually the fun will stop, “Goodbye pleasure, hello death.” The abyss is always there. But one does not need to face it alone.

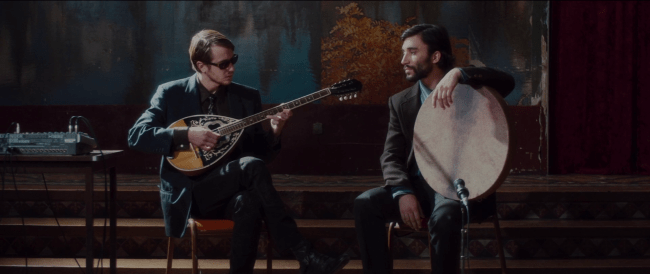

In essence, this is the journey of the film. We start with the pair of brothers, failed Greek musicians, who routinely end up at the unemployment office with a counselor who places them at various jobs and who himself harbors a musical passion. The Greek financial crisis is a background element to the film lending a certain weight to the instability of the brothers, but it never overwhelms. What goes further is the loyalty that the brothers feel toward their history, their traditions. The younger brother, played by Antonin Fresson, hides how good he is at playing the bouzoki from his older brother in order to spare his feelings – he is the inheritor of Marika Papagika’s talent. Two brothers against the world, struggling to live up to their forefathers. The two sisters rely on each other as well. One is blind, the other addicted to cocaine. The blindness is her abyss, but it not a tragic proposition – she can still hear, she has perfect pitch. When Bastien Bouillon’s Theo ceases to speak near her, Elise can still smell his perfume. And when he finds himself unable to tell her the truth, she grows uneasy, “It’s strange… this silence. What is happening?” In silence, there is a true abyss.

What fills this abyss? Companionship, laughter, emotion. The proposition is archaic (the plot could belong to the 1930’s), but Ropert attacks it with gusto. And I do mean attack sincerely. If her touch was light in previous films, here her gestures land like sharp jabs, a little cruder. The battle of the sexes is verbal – the brothers put down the sisters routinely, the sisters label them losers. There is a bet here to play with the codes of the romantic comedy and bend them toward something a little distasteful. To pretend to be blind, as Theo does, to play a trick on someone is almost predatory, but soon enough the image itself becomes rather ridiculous. It’s a school yard taunt that soon dissolves into something else entirely. It might start as a game, but when he sees her vulnerable face before him this is when something real can occur.

Another jab. When Serge Bozon appears as a rocker neighbor he casually dismisses the rebetiko music that Theo plays (as well as the practice of showering, he will not conform to society’s expectations!) and generally plays up his image, with Elise falling in line to his bad boy charm. Theo explodes, defending the rebetiko music, its importance, and also trying to put down Bozon (“he will never tell you if you have lettuce on your teeth”). When a sullen youth smoking marijuana complains that he wants to die, this is the ultimate sin, Theo berates him and tells him that life is immense, even when it appears small, and it is full of surprises.

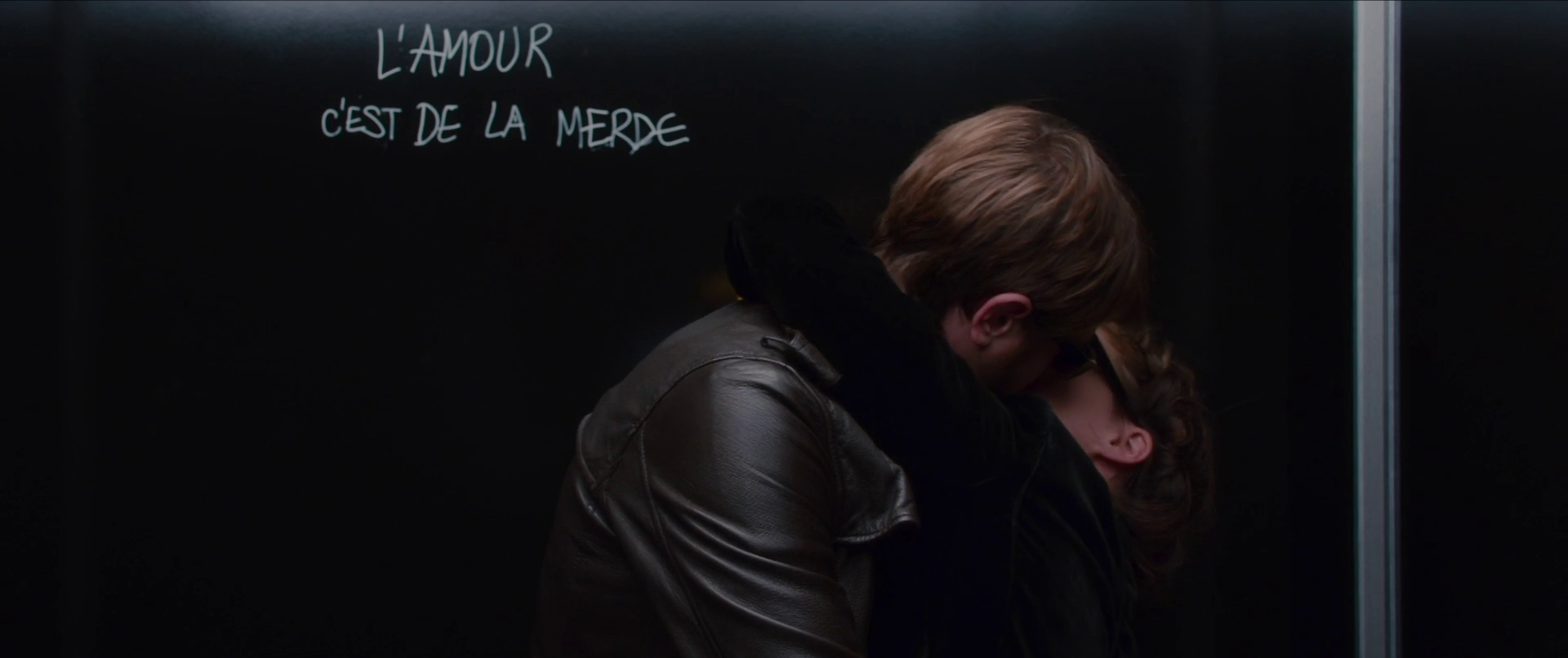

What to make of this? Sincerity placed right alongside, pushed against, really, a calculated artifice. If we are dealing with a romantic comedy, then we must understand how to navigate its codes. The artifice I refer is less of a stylistic one (Ropert does not need exaggerated effects) but rather one of the world itself. There is invention at every turn. Consider the elevator. Here is an obvious set with its own attendant color scheme and the recurring gag of the text written on the wall. The major characters all congregate here, the two brothers and two sisters, this is where they meet. The relationship begins here as does the deception which triggers the plot. Moreover, it is also the place where the younger brother begins to court, in a frankly ridiculous way, Elise’s sister, by complimenting her earrings. With each return to the elevator the relationship advances, through insults, through compliments, through silence. The elevator becomes a space for fiction.

Although the jokes can be brusque and sometimes in poor taste (strangers take advantage of the character’s blindness to steal their food), the spirit is gentle and triumphant. The characters reject the paths that have been laid before them, the past which weighs on them, and choose a path for themselves. But the path they choose lies in the path of tradition itself – they choose marriage. How to renew the traditions one finds themselves in? How to find their place in them? This is the course that Axelle Ropert sets herself in this film.

Alone Again (Naturally)

Tirez la langue, mademoiselle (Miss and the Doctors) takes place in the Chinatown district in Paris, a neighborhood where Axelle Ropert lives and “knows like the back of my hand.” Our first introduction comes over the opening credits, a shot from up high, seeing the pedestrians walk by, a SushiMagic in the background. And from there we will get acquainted more fully with its streets, its storefronts, its light, as we accompany its main characters (two brothers, both doctors, Cédric Kahn and Laurent Stocker) on their rounds. We become intimately acquainted with the path taken to visit by Dimitri (Stocker) to attend his Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The characters walk at night, heading home from playing ping pong, heading to work, stopping by to eat soup at a Cantonese restaurant, passing the soccer courts, neon advertising signs. There is a simple pleasure in seeing its characters do these things – it situates the romantic underpinnings of the film’s universe in the quotidian, in the everyday. The distinction I’m making is clear because the film is not really a romance, but it has a romantic streak running through it and it comes alive because how rooted the film is in the rhythms of its neighborhood, in the vistas of those nighttime strolls.

And this romantic streak is made literal, made visceral, the first time we see Judith (Louise Bourgoin) walking in the crowd, her red coat cutting through the bland environment, focusing our attention on her and nothing else. The images are documentary, caught on the fly with the small digital cameras, but the feeling is iconic. There is not a defeated position before the realities of contemporary auteur filmmaking – she rediscovers the power of the actor, as a tool, as a figure, by finding their glamour, “Making an actress look beautiful is totally essential to me.”

That red coat… one simple prop can make everything make sense, one small detail. Witness the close-ups to Judith removing her gloves in front of each brother. Of course, the two brothers immediately become smitten with her. But the path is complicated. The stakes are those of the romance, but the characters are far too unruly to conform to a formula and the world is too sad a place for romance to win out without leaving some casualties along the way. Desire often flows one way – a member of the AA meeting invites Dimitri to stay the night; the doctor’s assistant is in love with Boris (Kahn); he turns his head ever so slightly to see Judith walk away from him at the restaurant. A few furtive glances and encounters are all it takes for an obsession to form, perhaps even love. And from there desire must be negotiated in the real world of adults. The everyday world takes its toll, our jobs take a toll – Boris has a terrible day because he thinks one of his patients dislikes him and wants to leave him; Dimitri sees Boris feeling down and worries constantly, leading him to want to attend a meeting; Boris notes that Judith’s face changes when she talks about her daughter, a silent pressure, a suffering that remains unspoken. Everyone carries around baggage that cannot just be ignored in the face of desire, a romantic fantasy. This is the project, this is the beauty, of the film. It’s a film that lives with its sadness, approaching the limit of how life can be lived between its characters and determines to find a way forward for all of them.

The milieu dictates the melancholy spirit of the film. The doctors live in a world of illness, death and pain. The doctors become involved with Judith because of her daughter, a diabetic. There is Serge Bozon’s character who has early-onset MS and is scared of dying. Dimitri’s alcoholism is inescapable (Judith can tell because of his misty eyes, she’s reminded of her dead brother). Ropert escapes a miserabilist atmosphere and outlook by playing this against the colors of her film (the brightly-lit walls with soft colors, the neon-lights of the neighborhood), situating this rather dolorous world of missed opportunities and thwarted desire against the beautiful and hypnotic mise en scene (only one scene feels misplayed, where Bozon has to act as a go-between with the brothers in a somewhat clumsy handheld shot).

This is a film full of characters who care deeply about one another, who care deeply about how the other feels, and this drives their actions. Boris lets Dimitri pursue Judith even though he himself is in love with her. Judith’s daughter hides how she’s feeling because she doesn’t want to worry her mother. But the depth emotion can also suggest violence. When Dimitri takes the information of a man they’ve both realized is Judith’s ex-husband, he carefully looks at Boris – the look isn’t one of glee, really, but there is a bit of spite there. The quiet hurt in Boris’ eyes when Judith asks him something that could potentially derail their relationship. The assistant making it clear exactly how she feels (“Why do you only like sick people?”). But who is sick, really? And what is the sickness, exactly? Is it love? Or, rather, the idea of love? Something like companionship. The film tells two stories – one of an union, and one of a separation. And the union is only possible due to that separation. Perhaps in the end only a few select people can be truly happy, and to gain that happiness others must sacrifice. Is it a sickness to want to love enough to leave others behind? Is it a sickness to love enough to walk away, so you can preserve that love?

There’s a scene about halfway into the film where both doctors are seen at work, with the camera placed on the outside of the office, looking in through the glass, both of them seen through the drapes. The camera zooms in slowly on both of them as they take a look outside their window, facing the neighborhood. What do they take from this moment? What do they take from their neighborhood? Are they replenished by seeing people walk by, the natural bustle of city life? This place where you can run into the woman you love by accident as you walk home, just as easily as you can run into a drunk who is helpless out on the street? Where two minor characters can come together for a bit and talk about the brothers and wonder to themselves if they are happy now? The mystery of the film lies in this gesture – what happiness did they reach, or did they reach any at all?